Pave Frans: Elektroniske messer er en farlig nødløsning

Sandro Magister skriver om pave Frans’ ambivalente forhold til elektroniske (streamede) messer, bl.a.:

On March 12, Pope Francis had all the churches of his diocese of Rome closed, on account of the coronavirus pandemic. But he immediately regretted it, and the day after he had them reopened. But the ban has stayed in place, in Rome and Italy, on celebrating Masses with the faithful present. …

… The pope’s Masses are broadcast electronically. Those of Francis with the highest viewership levels, never reached in the past. Each of his Masses at Santa Marta, at 7 in the morning, is seen by about 1.7 million viewers.

Even on this, however, serious fears have now arisen in Francis. The apparent success of these televised Masses conceals a danger that many Catholics have already denounced. It is the danger that the sacrament may decay from real to virtual, and therefore dissolve. The cry of alarm has come not only from the currents most attached to tradition, but also from prominent exponents of the progressive wing, in Italy from the founder of the monastery of Bose Enzo Bianchi, from Church historian Alberto Melloni, from the founder of the Community of Sant’Egidio Andrea Riccardi.

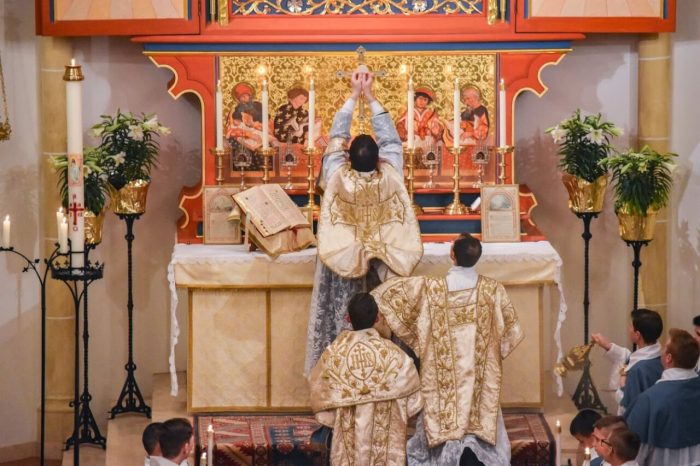

Well then, in the homily for the Mass at Santa Marta on April 17, Friday of the octave of Easter, Francis didn’t hold back anymore and explained that a “viralized” Church is no longer the true Church, made up of people and sacraments. Woe – he warned – if when the pandemic ends there remains alive the “gnostic” idea of a Church electronic rather than real.

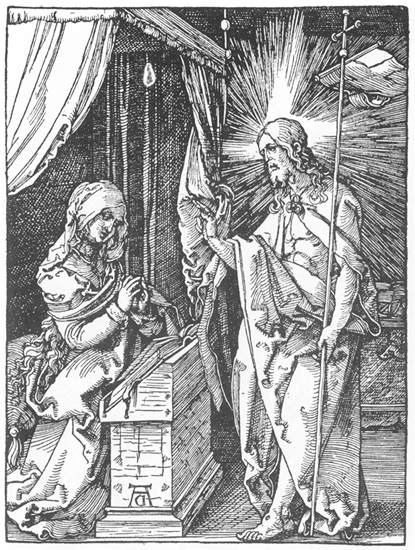

The pope’s homily is reproduced below. But first it may be useful to note that also in the past, when epidemics were raging, great pastors of the Catholic Church were aware of the need to keep the reality of the sacraments alive.

One can recall in this regard the great plague of Milan in 1576. Saint Charles Borromeo, the bishop, obtained from the Spanish governor of the city the obligation for all citizens to stay home for forty days. But he sent his priests to celebrate the Sunday Masses on the street corners, with the faithful looking on from doorways and windows.

Saint Charles also led processions, but with the foresight to arrange them in two single rows on the sides of the streets and with 3 meters of distance between each penitent. The chronicles of the time recall his continual visits to plague victims, but always with careful precautions. He changed very often and had his clothing boiled, purified everything he touched with fire and vinegar, kept his interlocutors at a distance with a wooden stick. It was calculated that in Milan there were 17,000 dead, compared with 70,000 in Venice. …

Her er et sitat fra pavens preken denne dagen, 17. april:

… This familiarity with the Lord, of Christians, is always communal. Yes, it is intimate, it is personal, but in community. A familiarity without community, a familiarity without the Bread, a familiarity without the Church, without the people, without the sacraments is dangerous. It can become a familiarity – let’s say – that is gnostic, a familiarity for me alone, detached from the people of God. The familiarity of the apostles with the Lord was always communal, was always at the table, a sign of community. It was always with the Sacrament, with the Bread.

I say this because someone made me reflect on the danger that we are living through at this time, this pandemic that has gotten all of us communicate, even religiously, through the media, through the channels of communication, even this Mass, we are all communicating, but not together, spiritually together. The people is small. There is a great people: we are together, but not together. Even the Sacrament: today you have it, the Eucharist, but the people who are connected with us, only spiritual communion. And this is not the Church: this is the Church of a difficult situation, which the Lord allows, but the ideal of the Church is always with the people and with the sacraments. Always. …