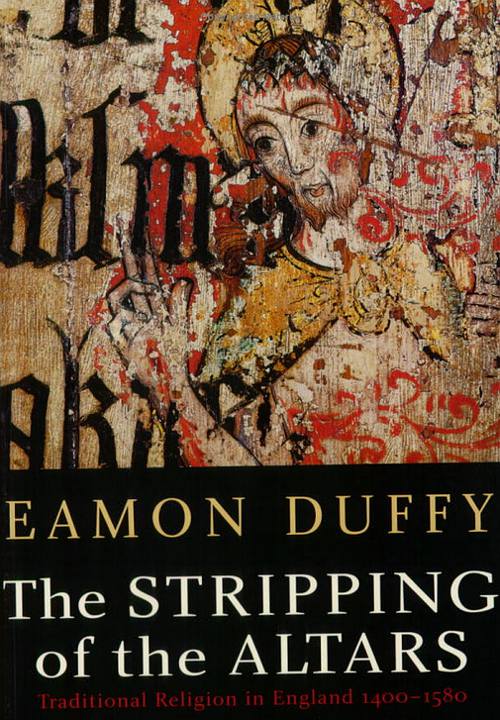

Jeg har nå lest 2/3 av Eamon Duffys bok «The Stripping of the Altars». Jeg er ferdig med første halvdel av boka, som tar for seg kirkelig og liturgisk praksis i England fram til 1530, og kommet et stykke inn i hva som skjedde etter kong Henriks brudd med paven, lest om flere av reformene (men det var ganske uklart de første årene om de protestantiske tendensene kom til å føre fram til endelige resultater. Jeg har bl.a. lest at hl Thomas Beckets relikvier i Canterbury var blitt ødelagt; graven åpnet, beina knust og spredd for alle vinder. Slik skriver Wikipedia om denne viktige boka:

…. The main thesis of Duffy’s book is that the Roman Catholic faith was in rude and lively health prior to the English Reformation. Duffy’s argument was written as a counterpoint to the prevailing historical belief that the Roman Catholic faith in England was a decaying force, theologically spent and unable to provide sufficient spiritual sustenance for the population at large.

Taking a broad range of evidence (accounts, wills, primers, memoirs, rood screens, stained glass, joke-books, graffiti, etc.), Duffy argues that every aspect of religious life prior to the Reformation was undertaken with well-meaning piety. Feast days were celebrated, fasts solemnly observed, churches decorated, images venerated, candles lit and prayers for the dead recited with regularity. Pre-Reformation Catholicism was, he argues, a deeply popular religion, practiced by all sections of society, whether noble or peasant. Earlier historians’ claims that English religious practice was becoming more individualised (with different strata of society having radically different religious lives) is contested by Duffy insisting on the continuing ‘corporate’ nature of the late medieval Catholic Church, i.e. where all members were consciously and willingly part of a single institution.

Much previous historical work on the Reformation, says Duffy, assumed it was a straightforward progression from the decaying Catholicism to the more morally pure but also more functional Protestantism. Duffy acknowledges that his thesis demands explanation of how, given the popularity of Catholicism, Protestantism was able to wipe away centuries of accumulated tradition, and do so in an incredibly short space of time. Duffy does this by proposing what he feels are a number of salient explanations — the political power of the militant Protestant clergy undertaking visitations to England’s parishes and that continued loyalty to the monarch allowed the word of the King to play a significant role in influencing public behaviour. Duffy also articulates the fact that while Catholics had the capability of rebelling against laws and edicts it was difficult for such rebellion to be sustained; there were simply no concepts of revolution or working-class solidarity by which Catholics could provide continued resistance to unpopular events.

The second part of Duffy’s book concentrates on the accelerated implementation of Protestantism in the mid sixteenth century. It charts how society reacted to Henrician, Edwardian and Elizabethan reform and the changes in religious practice this entailed. Duffy uncovers a succession of records, notes and images that individually reveal an assortment of changes to liturgy and custom but taken together build up to demonstrate a colossal change in English religious practice.

So we see how candlesticks and church plate had to be melted down and sold off, altar tables removed, rood screens defaced or torn down and chasubles unstitched. How walls were whitewashed, relics discarded and paintings of saints hidden in parishioners’ houses. And we also read how the other aspects of the Catholic community, such as the guild groups or particular local feast days, quickly collapsed without the economic or religious practices on which they depended. It was a painful process for Catholics, and Duffy vividly illustrates the confusion and disappointment of Catholics stripped of their familiar spiritual nourishment. …