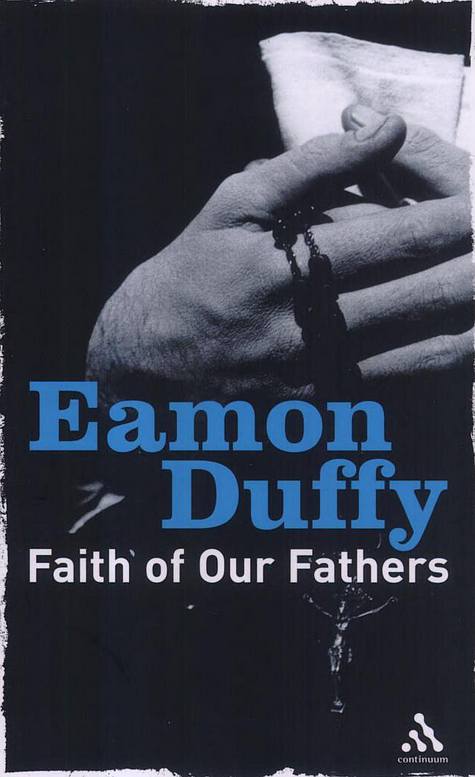

Faith of Our Fathers – forord

Eamon Duffy er en dyktig kirkehistoriker; har studert katolske praksis i England rundt reformasjonen svært grundig, har skrevet lange bøker om pavene og også reflektert over forholdet med sitt eget kjennskap til irsk katolisisme på 50- og 60-tallet. I forordet til boka ‘Faith og Our Fathers’ skriver han:

Roman Catholics have always attributed a special value to their Church’s past, for they believe that the saving truth of God is encountered not merely in the pages of the Bible, but in the proclamation, worship and shared experience of the Christian community — that complex expression of lived faith which we call the tradition. Yet in the latter twentieth century the Catholic Church underwent a dramatic and, to many, disturbing transformation, which seemed to open up a deep gulf between modern believers and their past. Anyone raised a Catholic before 1965 was formed in a Church which understood and presented itself as essentially timeless, its worship and its law enshrined (or, from another perspective, entombed) in the immemorial splendours of the Latin language, its authority structures dominated by its clergy, its principal teachings infallible and therefore irreformable. Roman Catholics had little contact with Christians from other traditions, and were indeed forbidden to worship or even to recite the Lord’s Prayer in common with them. A ‘fortress mentality’ prevailed, Church against world, which in Britain and in America was underpinned by the ethnic and social history of Catholics, many of whom were first-, second- or third-generation descendants of economic migrants, not always entirely at ease in the society around them.

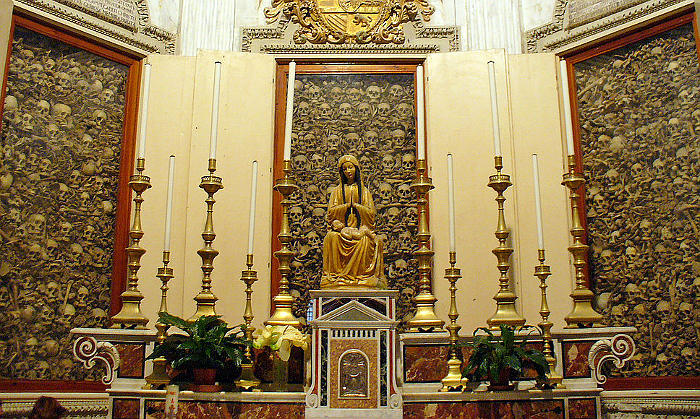

The reforms initiated by the Second Vatican Council, which met from 1962 to 1965, profoundly changed the experience of Catholics at every level. The monolith seemed to crumble, immobility gave way to flux. In the wake of the Council, worship was simplified and translated into the vernacular, and almost overnight the Latin liturgy, with its millennia-long repertoire of sacred music, became an exotic rarity: plainchant and renaissance polyphony were replaced by folk hymns accompanied by guitar and electronic keyboard. Catholic churches were ‘reordered’ to allow the clergy to face the people across the altar, and much of their traditional liturgical furniture and imagery was discarded as redundant. These ritual and organizational changes reflected profound theological reorientation as the older certainties of the seminary textbooks were challenged and replaced by theologies which emphasized engagement with social issues and openness to other Christians. Catholics were now encouraged to throw themselves into ecumenical activity, and structures were democratized to give lay people greater scope for involvement.

The religious ferment which began in the mid-1960s was part of a much wider social and cultural unsettlement. The sexual revolution which began then found its more decorous counterpart in the Roman Catholic debate over artificial methods of birth control, and the rethinking of authority and hierarchy with which Catholics were wrestling was inevitably influenced by the widespread suspicion of power and the structures of power which were the special mark of the 1960s and 1970s. It was an exhilarating time, filled with the sense of momentous and life-giving transformations, the bursting of constraints and the opening of new possibilities. For many who lived through them, myself included, these were unforgettable and formative years. But it was also a time of naive and sometimes philistine incomprehension of the past which had formed us, in which much that was precious was disparaged or discarded. In this atmosphere, to suggest that an idea or an institution was old-fashioned was often enough to discredit it. ‘Pre-Conciliar’ became a term of abuse or dismissal. It is now possible to see just how wholesale and indiscriminate this communal repudiation of the past was, and in a Church which claims to set a high theological value on tradition and continuity, this is a mystery which needs explanation. …