Jeg forsøger at være åben over for sandheden og vil altid gerne lade mig korrigere af kilderne, siger den tyske historiker Hubert Wolf, der forsker i Pius XII og holocaust.

Kirken har ingen grund til at frygte historien, sagde Vatikanets chefbibliotekar, kardinal José Tolentino Calaςa de Mendonςa, før Vatikanet den 2. marts i år åbnede for adgang til arkiver med millioner af dokumenter fra pave Pius XIIs pontifikat fra 1939 til 1958.

Langtfra alle vil være enige med ham, for siden Rolf Hochhuths skuespil Der Stellvertreter (Stedfortræderen 1963) har der været heftig strid om denne paves eftermæle. Der Stellvertreter fældede en knusende dom over Pius XII ved at anklage ham for fej tavshed og indirekte medskyld i millioner af jøders død. Den dom tog tyskerne til sig dengang i 1960’erne. Ja, i grunden brugte de den til at frikende sig selv med. Det skete, fordi tyskerne dengang var begyndt at bearbejde, hvad der egentlig skete under krigen. De tænkte: Ja, når ikke engang Kristi Stedfortræder protesterede højlydt, hvad i alverden skulle vi så kunne have gjort, siger Hubert Wolf, præst og professor i kirkehistorie i Münster i et interview den 22. april med avisen die Zeit.

I efterkrigstiden og ved sin død blev Pius XII omtalt særdeles positivt af jødiske ledere – blandt andet af Golda Meir. Man fremhævede hans valg af det stille diplomati, hvor der bag kulisserne blev arbejdet på at redde hundredtusinder af jøders liv. Et eksempel er Roms Schindler – den tyske pater Pankratius Pfeiffer, der efter direkte ordre fra paven hjalp forfulgte jøder og skjulte dem i Kirkens klostre og kirker.

Efter Hochhuth har der stået strid om Pius XII. Den britiske historiker John Cornwell gik så langt, at han i 1999 kaldte ham Hitler’s Pope i en bog med samme navn. Her argumenterer Cornwell for, at hele Pius XIIs karriere var dikteret af et ønske om at øge og centralisere pavestolens magt. Det var hans første prioritet, og kampen mod nazismen var underordnet dette mål. Cornwell hævdede også, at Pius XII var antisemit.

Da der blev åben adgang til Pius XIIs arkivalier, fik et tysk historikerhold under Wolfs ledelse 7 af 30 pladser på Vatikanarkivernes læsesal. De tyske historikeres store forskningsprojekt er finansieret af Kruppstiftelsen og Den tyske Bispekonference. Tyngdepunktet i undersøgelsen skulle ligge på, hvor meget Vatikanet vidste om Holocaust. For lettere at kunne overskue bjergene af arkivalier i Vatikanets arkiver fordelte det tyske historikerteam opgaverne indbyrdes og mødtes hver dag for at konferere om deres arkivfund.

Desværre blev det i denne omgang kun til fem dages studier, fordi coronapandemien satte en stopper for aktiviteterne. Det er planen, at forskerholdet fra Münster også skal se på, om Vatikanet hjalp førende krigsforbrydere til Sydamerika over den såkaldte Rattenlinie (rottelinjen). Ligeledes vil teamet granske i forholdet mellem Vatikanet og staten Israel. Israel blev som bekendt grundlagt i 1948, men blev først anerkendt af Vatikanet i 1993. Her håber man på at finde nyt arkivmateriale, der kan belyse, hvad der egentlig skete bag kulisserne.

Hubert Wolf har de sidste 30 år arbejdet med Vatikanets arkiver især angående Pius XII (Eugenio Pacelli). Under hans ledelse arbejdede et team fra Münster i 12 år med en kritisk online-udgave af Pacellis indberetninger til den romerske kurie i tiden som nuntius i Bayern og senere Berlin fra 1917 til 1929.

Wolf vil som historiker gerne stille åbne spørgsmål, men lægger ikke skjul på, at han er inde i lidt af et minefelt. ”Jeg forsøger at være åben over for sandheden og vil altid gerne lade mig korrigere af kilderne. Men hvad der virkelig har gjort både mig og mit team dybt bedrøvede, var de mange bønskrifter. Hver af os har bestemt læst fem, seks, syv skrivelser, der indtil nu har været ukendte, hvor jøder mellem 1940 og 1945 trygler paven om at redde deres liv. De beskriver deres udsigtsløse situation og beder indtrængende om hjælp”, siger Wolf, som fra 2007 til 2016 var særlig rådgiver for Den tyske Bispekonferences kommission for Den katolske Kirkes relationer til jødedommen. Han har planer om at etablere et samarbejde med det jødiske universitet i Heidelberg om en digitalisering af kilderne om Pius XII og holocaust.

Saligkåringsprocessen for Pius XII har stået på, siden Paul VI tog initiativ til den i 1965. I 1990 blev han erklæret for servus Dei (Guds tjener) og i 2009 for venerabilis (ærværdig). Hubert Wolf er blandt dem der mener, at saligkåringsprocessen må sættes i bero, indtil man har arbejdet sig gennem dokumenterne.

Respekten for Holocaustofrene, men også for Pius XII selv kræver grundigt forarbejde, før der kan konkluderes på noget, siger Wolf i et interview med Domradio.de.

……

……

Wolf er som sagt klar over, at han bevæger sig i et minefelt og regner med, at vi først kan vente seriøse resultater fra arkivarbejdet om tre til fem år.

Og der er dokumenter til mange års arbejde i arkiverne. Lige nu ligger den største opmærksomhed på Holocaust-tiden; men dokumenterne vil også indeholde værdifuld viden om atombomberne over Japan i 1945, den kolde krig, afviklingen af kolonierne og udviklingen i katolsk teologi – for eksempel omkring Mariadogmet i 1950 og Kirkens stilling til den historisk-kritiske bibelforskning.

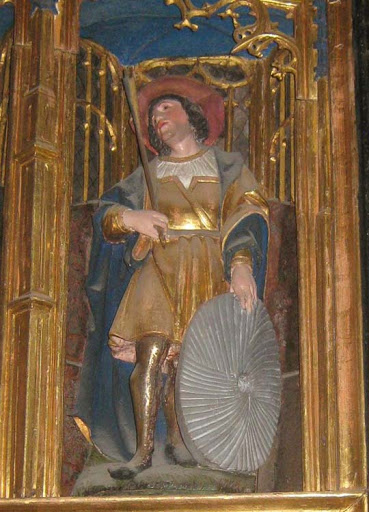

Kildematerialet om Hallvards liv og helgendyrkelsen av ham gjennom fire hundre år før reformasjonen (og etter) er både billedlig og bokstavelig talt fragmentert. To av fire hovedkilder er skrevet på pergament som senere er blitt klippet opp til bokbind, såkalte permfyllinger. Det ene fragmentet befinner seg i det norske Riksarkivet, det andre i det svenske. I motsetning til Olav Haraldsson som ble helligkåret som den første i Norge, var det ingen skalder som fulgte i Hallvards følge og kunne levere beretninger for ettertiden. Snorre behandler Hallvard kun i kortversjon. På tross av dette kan man følge Hallvard gjennom hele middelalderen i spredte tekster og beskjedent, men viktig billedmateriale.

Kildematerialet om Hallvards liv og helgendyrkelsen av ham gjennom fire hundre år før reformasjonen (og etter) er både billedlig og bokstavelig talt fragmentert. To av fire hovedkilder er skrevet på pergament som senere er blitt klippet opp til bokbind, såkalte permfyllinger. Det ene fragmentet befinner seg i det norske Riksarkivet, det andre i det svenske. I motsetning til Olav Haraldsson som ble helligkåret som den første i Norge, var det ingen skalder som fulgte i Hallvards følge og kunne levere beretninger for ettertiden. Snorre behandler Hallvard kun i kortversjon. På tross av dette kan man følge Hallvard gjennom hele middelalderen i spredte tekster og beskjedent, men viktig billedmateriale.

Etter 20 års sammenhengende innsats er biograf Tor Bomann-Larsen nå ute med åttende og siste bind i sitt monumentale kongebiografi-verk «Haakon og Maud».

Etter 20 års sammenhengende innsats er biograf Tor Bomann-Larsen nå ute med åttende og siste bind i sitt monumentale kongebiografi-verk «Haakon og Maud». Den unge Joseph er temmelig indadvendt og flygter ind i bøgerne. Yndlingsbogen bliver Hermann Hesses Klassiker Steppeulven – senere hippiernes kultbog. Han skriver digte, og som seminarist er han igennem en langvarig forelskelse, før han beslutter sig for at blive præst. ”Ja, jeg er blevet berørt af kærligheden i dens forskellige dimensioner og former. At være elsket og give andre kærlighed tilbage har jeg mere og mere oplevet som helt grundlæggende”, siger pave Benedikt, og Seewald spørger ham direkte: ”Var De forelsket i en pige? Måske. Altså ja? Man kunne udlægge det sådan. Hvor længe varede så denne lidelsesfulde tid? Nogle uger? Et par måneder? Længere.”

Den unge Joseph er temmelig indadvendt og flygter ind i bøgerne. Yndlingsbogen bliver Hermann Hesses Klassiker Steppeulven – senere hippiernes kultbog. Han skriver digte, og som seminarist er han igennem en langvarig forelskelse, før han beslutter sig for at blive præst. ”Ja, jeg er blevet berørt af kærligheden i dens forskellige dimensioner og former. At være elsket og give andre kærlighed tilbage har jeg mere og mere oplevet som helt grundlæggende”, siger pave Benedikt, og Seewald spørger ham direkte: ”Var De forelsket i en pige? Måske. Altså ja? Man kunne udlægge det sådan. Hvor længe varede så denne lidelsesfulde tid? Nogle uger? Et par måneder? Længere.”