De italienske biskopen har vært sammen i Assisi denne uka, og pave Benedikt sendte dem en hilsen, der han ikke bare hilste vennlig på dem, men også tok opp viktige liturgiske spørsmål. Zenit.org har oversatt brevet til engelsk, og her er litt av det:

… The Fourth Lateran Council itself, considering with particular attention the sacrament of the altar, inserted in the profession of faith the term «transubstantiation,» to affirm the presence of the real Christ in the Eucharistic sacrifice: «His Body and Blood are truly contained in the Sacrament of the altar, under the species of bread and wine, as the bread is transubstantiated into the Body and the wine into the Blood by the divine power» (DS, 802).

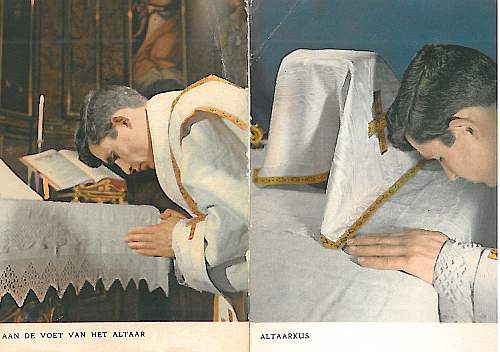

From attendance at Mass and reception with devotion of Holy Communion springs the evangelical life of St, Francis and his vocation to follow the way of the Crucified Christ: «The Lord — we read in the Testament of 1226 — gave me so much faith in the churches, which prayed simply thus and said: We adore you, Lord Jesus, in all the churches that are in the whole world and we bless you, because with your Holy Cross you have redeemed the world».

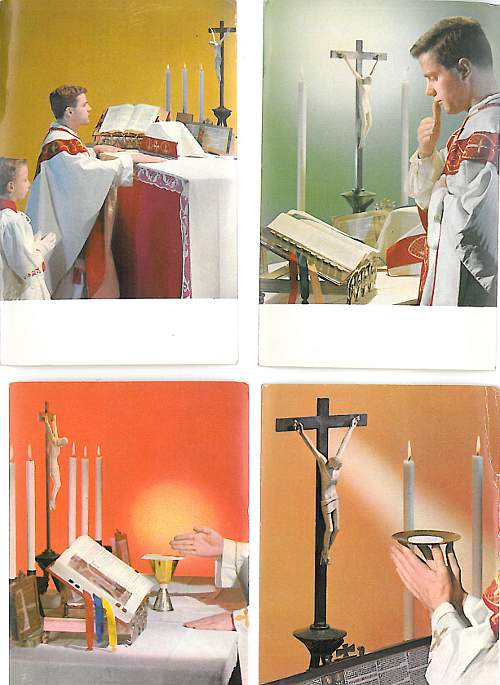

Found also in this experience is the great deference that he had toward priests and the instruction to the friars to respect them always and in every case, «because of the Most High Son of God I do not see anything else physically in this world, but his Most Holy Body and Blood which they alone consecrate and they alone administer to others»

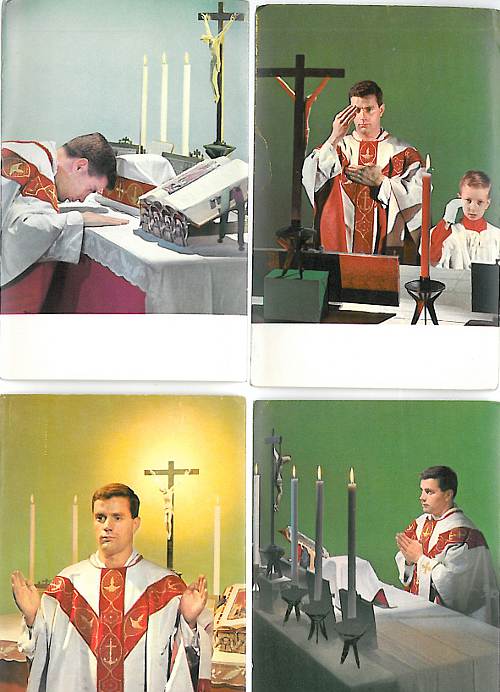

Given this gift, dear brothers, what responsibility of life issues for each one of us! «Take care of your dignity, brother priests,» recommended Francis, «and be holy because He is holy». Yes, the holiness of the Eucharist exacts that this mystery be celebrated and adored conscious of its greatness, importance and efficacy for Christian life, but it also calls for purity, coherence and holiness of life from each one of us, to be living witnesses of the unique Sacrifice of love of Christ.

The saint of Assisi never ceased to contemplate how «the Lord of the universe, God and Son of God, humbled himself to the point of hiding himself, for our salvation, in the meager appearance of bread», and with vehemence he requested his friars: «I beg you, more than if I did so for myself, that when it is appropriate and you regard it as necessary, that you humbly implore priests to venerate above all the Most holy Body and Blood of Our Lord Jesus Christ and the holy names and words written of Him that consecrate the Body».

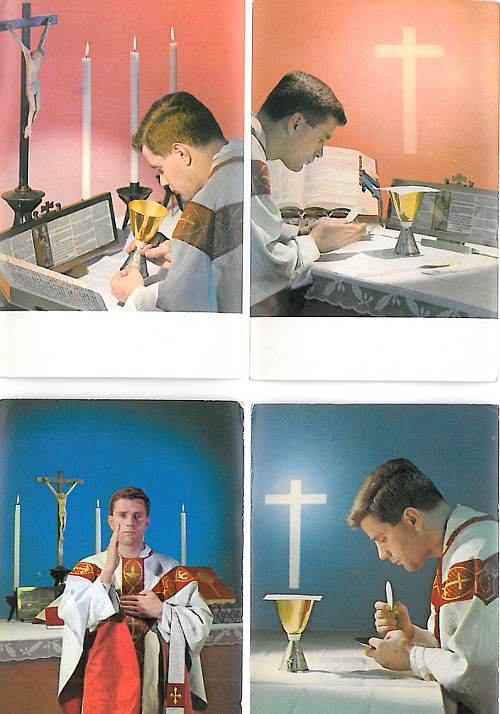

The genuine believer, in every age, experiences in the liturgy the presence, the primacy and the work of God. It is «veritatis splendor», nuptial event, foretaste of the new and definitive city and participation in it; it is link of creation and of redemption, open heaven above the earth of men, passage from the world to God; it is Easter, in the Cross and in the Resurrection of Jesus Christ; it is the soul of Christian life, called to follow, to reconciliation that moves to fraternal charity. ….