La meg begynne med et eksempel som ligner en del: Når ortodokse kirker ønsker fullt fellesskap med paven og Den katolske Kirke, så må de forandre sine synspunkter på pavens plass, hvordan Kirken ledes, og underlegge seg dens struktur og disiplin. Men de kan beholde 100% av sin liturgiske tradisjon, teologi og sine biskoper. Når protestanter søker enhet med Den katolske Kirke (og nå tenker jeg mest på anglikanere og lutheranere), må de selvsagt oppgi en hel del mer, men det skulle også være mulig å la dem få beholde mye fra sin egen tradisjon.

Etter Vatikankonsilet var det samtalene med anglikanerne (bildet over er fra 1966) som kom raskest i gang (og man må nok i dag kunne si at man var overoptimistiske), mens samtalene med lutheranere kom mer gradivis, men ble etter hvert svært fruktbare. Og til noen anti-økumener som av og til kommeneter på denne bloggen: Man misforstår nok pave Paul VI når man tolker hans uttrykk «united but not absorbed» som noe annet enn det jeg har skrevet over – at man på alle punkter godtar den katolske lære, men samtaidig kan få beholde tradisjoner som er forenlige med denne lære.

Etter Vatikankonsilet var det samtalene med anglikanerne (bildet over er fra 1966) som kom raskest i gang (og man må nok i dag kunne si at man var overoptimistiske), mens samtalene med lutheranere kom mer gradivis, men ble etter hvert svært fruktbare. Og til noen anti-økumener som av og til kommeneter på denne bloggen: Man misforstår nok pave Paul VI når man tolker hans uttrykk «united but not absorbed» som noe annet enn det jeg har skrevet over – at man på alle punkter godtar den katolske lære, men samtaidig kan få beholde tradisjoner som er forenlige med denne lære.

Det er det jeg har har introdusert så langt, som William Oddie skriver om i et innlegg i The Catholic Herald:

Some cradle Catholics still just don’t get it. Why do they want their own little enclave: if they want to be Catholics, why don’t they just join? What is this stuff about an Anglican “patrimony”? Isn’t that just what they want to get away from?

The first thing to say about the usage of Anglican “patrimony” is that it wasn’t coined by an Anglican, but by Pope Paul, in the days before the aspiration of an eventual corporate reunion of Canterbury and Rome (always, with the benefit of hindsight, an impossible dream) had been rudely shattered by the Anglicans’ unilateral decision fundamentally to redefine their orders in a way impossible for Catholics ever to accept.

But in those days, the ordination of women seemed a very distant – and unlikely – possibility which many (I was one of them) chose to ignore. The way forward to reunion seemed to be open; the pace seemed to be quickening. At the beatification of the English and Welsh martyrs in 1970 (which offended many Anglicans at the time), Pope Paul went out of his way to make an overture to the Anglican tradition (of which he was a genuine admirer: he used to listen to LPs of Anglican church music in moments of relaxation). “There will,” he said, “be no seeking to lessen the legitimate prestige and usage due to the Anglican Church when the Roman Catholic Church … is able to embrace firmly her ever-beloved sister in the one authentic communion of the family of Christ…” He made it clear that what he called the “worthy patrimony” of Anglicanism would be preserved in a united Church. A few years later, he said that he believed that “these words of hope ‘The Anglican Church united not absorbed’ are no longer a mere dream”.

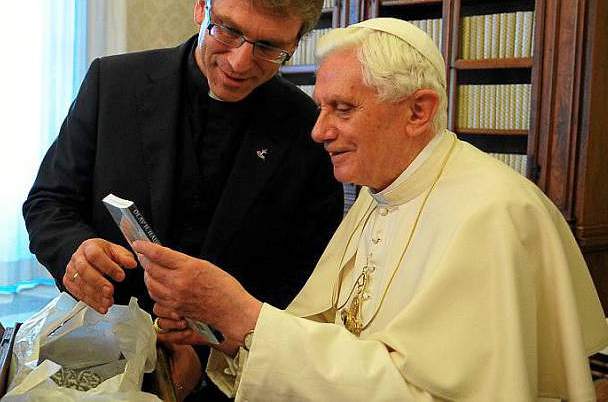

Alas, he was wrong. The wholesale reunion of Canterbury and Rome was always a mere dream; and soon it was brutally shattered. But Pope Paul’s vision of an Anglican “patrimony” united with the Catholic Church but (like the Eastern Catholic patrimony) not wholly absorbed, were not forgotten, either in Rome (where Cardinal Ratzinger remembered them) or by those Anglicans who for nearly two decades have been talking, firstly to him at the CDF, and then to his successors at the CDF who have remained in charge of the process throughout: it was their decision, entirely justified, that the English bishops should not be consulted, since they would have done everything they could to wreck it, as they had once before in the 1990s.

Vår egen biskop var på Den norske kirkes kirkemøte i går, og snakket varmt om de menneskelige relasjonene så nå fins mellom katolikker og lutheranere i Norge:

Vår egen biskop var på Den norske kirkes kirkemøte i går, og snakket varmt om de menneskelige relasjonene så nå fins mellom katolikker og lutheranere i Norge: Én av de fem anglikanske biskopene som har annonsert at de vil konvertere, forteller at det var pave Benedikts brev Angecalorum Cætibus som forandret situasjonen:

Én av de fem anglikanske biskopene som har annonsert at de vil konvertere, forteller at det var pave Benedikts brev Angecalorum Cætibus som forandret situasjonen: Etter Vatikankonsilet var det samtalene med anglikanerne (bildet over er fra 1966) som kom raskest i gang (og man må nok i dag kunne si at man var overoptimistiske), mens samtalene med lutheranere kom mer gradivis, men ble etter hvert svært fruktbare. Og til noen anti-økumener som av og til kommeneter på denne bloggen: Man misforstår nok pave Paul VI når man tolker hans uttrykk «united but not absorbed» som noe annet enn det jeg har skrevet over – at man på alle punkter godtar den katolske lære, men samtaidig kan få beholde tradisjoner som er forenlige med denne lære.

Etter Vatikankonsilet var det samtalene med anglikanerne (bildet over er fra 1966) som kom raskest i gang (og man må nok i dag kunne si at man var overoptimistiske), mens samtalene med lutheranere kom mer gradivis, men ble etter hvert svært fruktbare. Og til noen anti-økumener som av og til kommeneter på denne bloggen: Man misforstår nok pave Paul VI når man tolker hans uttrykk «united but not absorbed» som noe annet enn det jeg har skrevet over – at man på alle punkter godtar den katolske lære, men samtaidig kan få beholde tradisjoner som er forenlige med denne lære.