Den hellige dør: Pave Frans og pave emeritus Benedikt

Videoen under viser at pave Frans i går åpnet den hellige dør i Peterskirken, og at han og pave emeritus Benedikt går gjennom den.

Videoen under viser at pave Frans i går åpnet den hellige dør i Peterskirken, og at han og pave emeritus Benedikt går gjennom den.

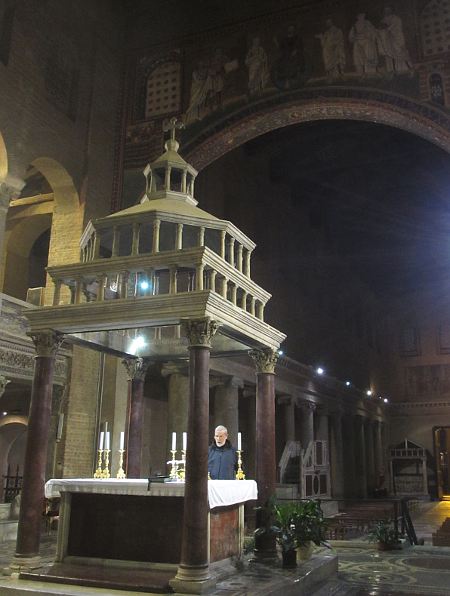

De siste ukene har jeg mange morgener feiret messe ved Jesu-hjerte-alteret i Peterskirken. Det er kort vei fra sakristiet til dette alteret, og siden jeg ber sakristanene om å lede meg til et ledig alter, blir det ofte dette – siden det nå (jeg merket det så snart november begynte) er færre mennesker både i Roma og i Peterskirken, og flere ledige altere.

De siste ukene har jeg mange morgener feiret messe ved Jesu-hjerte-alteret i Peterskirken. Det er kort vei fra sakristiet til dette alteret, og siden jeg ber sakristanene om å lede meg til et ledig alter, blir det ofte dette – siden det nå (jeg merket det så snart november begynte) er færre mennesker både i Roma og i Peterskirken, og flere ledige altere.

Om dette alteret kan vi lese følgende:

The Altar of the Sacred Heart, which on the occasion of St. Margaret Mary Alacoque’s canonization in 1923 (1920?), was decorated with a mosaic inspired by a painting by Carlo Muccioli (1857-1933).

På katolsk.no leser vi om henne bl.a.:

I mars 1824 ble Margareta Marias «heroiske dyder» anerkjent av pave Leo XII (1823-29) og hun fikk tittelen Venerabilis («Ærverdig»). Da hennes grav ble kanonisk åpnet i juli 1830 skjedde to øyeblikkelige helbredelser. Hun ble saligkåret den 18. september 1864 (dokumentet (Breve) var datert den 19. august) av den salige pave Pius IX (1846-78) og helligkåret den 13. mai 1920 av pave Benedikt XV (1914-22) sammen med den hellige Jeanne d’Arc. Hennes tålmodighet og tillit under prøvelsene bidro sterkt til hennes helgenkåring. Hennes minnedag er 16. oktober, siden dødsdagen den 17. er opptatt av den hellige Ignatius av Antiokia. Hennes navn står i Martyrologium Romanum.

Hennes visjoner og belæringer har hatt stor innflytelse på katolikkenes fromhetsliv, særlig etter at Jesu-Hjerte-festen ble forordnet for hele Kirken i 1856. Hun etterlot seg en kortfattet og rørende selvbiografi. Hun deler tittelen «Det hellige Hjertes helgen» sammen med den hellige Johannes Eudes og den salige Claude la Colombière. Hun avbildes i salesiansk ordensdrakt mens hun holder et flammende hjerte, eller mens hun kneler foran Kristus som viser frem sitt hjerte for henne.

På denne oversikten over Peterskirken er det alter nr. 44, og sakristiet er nr. 28.

John Allen skriver en artikkel der han stiller akkurat dette spørsmålet – og foreslår at fem ting kommer til å skje:

I did something that’s basically an act of madness: I delivered a set of predictions for 2016 regarding the almost metaphysically unpredictable Pope Francis. …

1. The next US cardinal Francis names will be a shocker.

It’s not clear whether Francis will create new cardinals in 2016, or whether one of them would be an American. If so, however, it probably won’t be anyone people are expecting — Archbishop Jose Gomez of Los Angeles, for instance, or Blase Cupich in Chicago.

When distributing red hats, Francis likes to bypass the usual centers of power. …

2. Francis will have a health issue.

So far, this pope has not had a serious health crisis. A bogus report in October of a benign brain tumor doesn’t count, since it fell apart almost as soon as it appeared.

On the other hand, Francis turns 79 on Dec. 17 and keeps up a schedule that would destroy people half his age. Those closest to Francis have long said they’re worried about the pope not taking care of himself, for instance by canceling his summer vacation at Castel Gandolfo. Watching him up close, he often seems visibly fatigued …

3. The pope will be a player in the US elections.

Pope Francis is likely to emerge as a major factor in the US elections in 2016, an especially plausible prospect given that five of the GOP contenders are Catholic (Jeb Bush, Rick Santorum, Marco Rubio, Chris Christie, and George Pataki; Bobby Jindal dropped out of the race in November).

One moment when the pope appears destined to inject himself into the race will come in February, when he travels to Mexico. The trip will feature a stop in Ciudad Juarez at the US/Mexico border, where Francis will make a major statement about immigration. …

4. The pope will make two significant gestures of mercy.

Francis opens his special jubilee Year of Mercy Tuesday, and at least two unscripted papal gestures of compassion may roll out at some point along the way.

First, he may offer a hand to divorced and civilly remarried Catholics. The question of whether they could receive Communion was hotly debated at the recent Synods of Bishops on the family, and while there was no consensus, there was agreement that the Church needs to do a better job of making them feel included.

Second, and possibly more quickly, Francis may offer pardons to least some of the five people currently facing a Vatican criminal trial for leaking secrets. …

5. Resistance to Francis’ initiatives will continue, but shift.

All along, there’s been resistance to Francis in some quarters inside and outside the Catholic Church. In 2016, that blowback will almost certainly continue, but it may become less about left vs. right and more about north vs. south and rich vs. poor.

A sign of things to come appeared before Francis’ November trip to Africa with a controversial essay by an editor for a web site operated by the largely progressive German bishops’ conference, suggesting that Francis may have an overly romanticized vision of the global South and an overly negative approach to Europe. …

Jeg har akkurat lest ferdig kapittel 2 i Matthew Leverings bok Sacrifice and Community (som jeg skrev om her), et kapittel han kaller The Eucharist and Expiatory Sacrifice. Her sier han først at reformert jødedom og noen moderne kristne teologer egentlig ikke ønsker å snakke om soning for synd i det hele tatt. Levering, derimot, siterer Aquinas og Paulus svært grundig og viser at og hvordan menneskenes synder måtte sones for Gud, og hvordan Kristi offer på korset gjorde akkurat dette. Deretter knytter han dette sonofferet til eukaristien, og viser hvordan dette offeret gjentas i messens hellige offer «not as a distinct oblation, but a commemoration of that sacrifice which Chist offered». Og så avslutter han kapittelet slik:

Jeg har akkurat lest ferdig kapittel 2 i Matthew Leverings bok Sacrifice and Community (som jeg skrev om her), et kapittel han kaller The Eucharist and Expiatory Sacrifice. Her sier han først at reformert jødedom og noen moderne kristne teologer egentlig ikke ønsker å snakke om soning for synd i det hele tatt. Levering, derimot, siterer Aquinas og Paulus svært grundig og viser at og hvordan menneskenes synder måtte sones for Gud, og hvordan Kristi offer på korset gjorde akkurat dette. Deretter knytter han dette sonofferet til eukaristien, og viser hvordan dette offeret gjentas i messens hellige offer «not as a distinct oblation, but a commemoration of that sacrifice which Chist offered». Og så avslutter han kapittelet slik:

… avoiding an idealist account of the Eucharist does require recognizing as the fulfillment of the «practice of Israel,» the expiatory character of Christ’s sacrifice within the created order constituted by relationships of justice. The Eucharist as a sacramental-sacrificial participation in Christ’s expiatory sacrifice, configures and nourishes Christ’s mystical body … (p 94)

I går hadde vi en fin tur til Castel Gandolfo, en kort togreise 20 km sørøst for Roma. Vi besøkte Palazzo Apostolico, der det var et fint museum som viste bilder og informasjon om pavene som hadde vært der, og også utstyr som ble brukt av pavene i tidligere tider. Fra «palasset» er det også flott utsikt over Lago Albano (som ett av bildene viser). Vi gikk også en lang tur rundt det meste av innsjøen – det var knapt 15 gr og lett overskyet.

Bildet over viser meg ivrig studerende, onsdag morgen 2. desember. Det var nydelig solskinn og behagelig å sitte ute fra kl 09 – litt før 12 ble det nesten litt for varmt, så jeg pakket sammen og gikk på kontoret (på Det Norske institutt). Det har blitt kaldere i Roma også de siste ukene, ganske kjølig etter kl 16, og sola går ned rundt kl 17 – men jeg forstår at det er en del bedre enn slaps o.l. i Norge. Vi har vært heldige og hatt mye fint vær i november, og også nå i starten av desember, mens det var noe mer regn i oktober – men da var det samtidig ganske varmt.

Jeg merker at det er lavsesong i Roma nå; det merker jeg tydelig når jeg feirer messe i Peterskirken om morgenen (07.30), og det er forholdsvis glissent på kafeer o.l. rundt om i byen. De som kjenner byen godt sier at det vil ta seg opp i midten av desember og holde seg ut januar. Februar er en rolig måned igjen, og så er det visst fullt av turister igjen fra mars og ut oktober.

Boka jeg leser på bildet er The Late Medieval English Church: Vitality and Vulnerability Before the Break with Rome, av G. W. Bernard. Amazon skriver om boka:

Boka jeg leser på bildet er The Late Medieval English Church: Vitality and Vulnerability Before the Break with Rome, av G. W. Bernard. Amazon skriver om boka:

The later medieval English church is invariably viewed through the lens of the Reformation that transformed it. But in this bold and provocative book historian G. W. Bernard examines it on its own terms, revealing a church with vibrant faith and great energy. Bernard looks at the structure of the church, the nature of royal control over it, the clergy and bishops, the intense devotion and deep-rooted practices of the laity, anti-clerical sentiment, and the prevalence of heresy. He argues that the Reformation was not inevitable, nor made unavoidable by the defectiveness, corruption, superstition or outdatedness of a church ripe for a fall: the late medieval church had both vitality and vulnerabilities, the one often linked to the other. The result is a thought-provoking study of a church and society in transformation.

Jeg har, som jeg skrev i går, begynt å lese Matthew Leverings bok Sacrifice and Community: Jewish Offering and Christian Eucharist. Her skriver Levering om sakramental/eukaristisk realisme eller idealisme, og starter med å undersøke hvordan Det nye testamente og den første kristne liturgien bygger på jødenes forståelse og tempeltjeneste. Det er tydelig at levering selv har mer tro på en liturgisk realisme heller enn en idealisme; slik omtaler og siterer han den jødiske teologen Wyschogrod, som skrev slik på 90-tallet:

For Wyschogrod, to conceive of a communion with God outside such sacrifice is to fall into rationalism. He writes: “Above all, sacrifice is not an idea, but an act. Prayer and repentance are ideas. They are contemplative actions, of the heart rather than the body. For this reason, rationalists of all times have been delighted by the termination of the sacrifices. For them, the “service of the heart” is self-evidently more appropriate for communication between man and their rational God than the bloodbaths of a Temple-slaughterhouse.”

It follows that the communion, from our side, is only real if sacrificial. Sacrificial worship affirms that communal sacrifice is the only posture in which we can, as creatures, truly enter into communion with God. Wyschogrod states: “Enlightened religion recoils with horror from the thought of sacrifice, preferring a spotless house of worship filled with organ music and exquisitely polite behavior. …”

Non-sacrificial communion involves neither the human being’s true (completely dependent) self, nor God’s presence transforming and embracing the full human being.

Jeg begynner nå å lese boka Sacrifice and Community: Jewish Offering and Christian Eucharist, skrevet av professor Matthew Levering og utgitt i 2005. Starten på bok virker lovende; Levering viser når og hvordan også katolske teologer (Luther hadde allerede gjort det) begynte å hevde at eukaristien hadde lite med offer å gjøre. (Det er ett av temaene jeg gjerne vil finne mer ut om disse studiemånedene.) På amazon.co.uk omtales boka bl.a. slik:

This book explores the character of the Eucharist as communion in and through sacrifice. Drawing on Jewish reflection upon the Aqedah (the near–sacrifice of Isaac by Abraham in Genesis), as well as on other critical analyses of sacrifice in Scripture, the book shows that communion is not possible without the reconciliation attained by sacrificial self–giving love. Following the insights of St Thomas Aquinas, the author argues that all aspects of Eucharistic theology, including metaphysical doctrines such as transubstantiation, depend upon recognizing that communion cannot be separated from its sacrificial context.

The book will stimulate discussion because of its controversial critique of the dominant paradigm for Eucharistic theology, its reclamation of St Thomas Aquinas s theology of the Eucharist, and its response to Pope John Paul II s Ecclesia de Eucharistia. …

Jon D. Levenson points out that Israel, marked by desire to be in communion with the all-holy God, recognizes that such communion is possible only, after sin, through sacrificial offering.

Jeg leste i dag tidlig en artikkel skrevet av P. Cassian Folsom, O.S.B., som tar opp dette temaet. Der skriver forfatteren bl.a.:

… For some 1600 years previously, the Roman rite knew only one Eucharistic Prayer: the Roman canon.

In the average parish today, Eucharistic Prayer II is the one most frequently used, even on Sunday. Eucharistic Prayer III is also used quite often, especially on Sundays and feast days. The fourth Eucharistic prayer is hardly ever used; in part because it is long, in part because in some places in the U.S. it has been unofficially banned because of its frequent use of the word «man». The first Eucharistic Prayer, the Roman canon, which had been used exclusively in the Roman rite for well over a millennium and a half, nowadays is used almost never. As an Italian liturgical scholar puts it: «its use today is so minimal as to be statistically irrelevant».

This is a radical change in the Roman liturgy. Why aren’t more people aware of the enormity of this change? Perhaps since the canon used to be said silently, its contents and merits were known to priests, to be sure, but not to most of the laity. Hence when the Eucharistic Prayer began to be said aloud in the vernacular, with four to choose from — and the Roman canon chosen rarely, if ever — the average layman did not realize that 1600 years of tradition had suddenly vanished like a lost civilization, leaving few traces behind, and those of interest only to archaeologists and tourists.

What happened? Why did it happen? How should we respond to the new situation? These questions are the subject matter of this essay.

Til spørsmålet om hvorfor dette skjedde, skriver han bl.a.:

1. Advances in liturgical studies

The first reason is quite straightforward. Decades of scholarly research in the area of the anaphora, both eastern and western, had resulted in a considerable corpus of primary texts and a corresponding body of secondary literature. …

2. Dissatisfaction with the Roman Canon and architectural functionalism

A second reason for the change from one Eucharistic Prayer to many was dissatisfaction, on the part of some liturgical scholars, with the Roman canon. I would like to argue that there is a connection between this dissatisfaction and 20th-century architectural functionalism.

The man who best illustrates this theory is Cipriano Vagaggini. In Vagaggini’s book on the Roman canon, prepared for Study Group 10 of the Consilium (the group responsible for implementing the Council’s reform), the basic argument in favor of change is that the Roman canon is marred by serious defects of structure and theology. Vagaggini summarizes his argument in these words: «The defects are undeniable and of no small importance. The present Roman canon sins in a number of ways against those requirements of good liturgical composition and sound liturgical sense that were emphasized by the Second Vatican Council.»

The structural defects show themselves in the disorderliness of the Canon, according to Vagaggini. It gives the impression of an agglomeration of features with no apparent unity, there is a lack of logical connection of ideas, and the various prayers of intercession are arranged in an unsatisfactory way. …

Not only is the Roman Canon marred by structural defects, according to Vagaggini, but there are a number of theological defects as well. The most grievous of these theological problems is the number and disorder of epicletic-type prayers in the canon and the lack of a theology of the part played by the Holy Spirit in the Eucharist.

Liturgical historian Josef Jungmann counters this critique of Vagaggini’s by pointing out that Vagaggini is a systematic theologian who wanted to impose a certain preconceived theological structure on the Eucharistic Prayer. Since Vagaggini had a particularly keen interest in the pneumatological dimension of the liturgy, his new Eucharistic Prayers (III and IV) give a decided emphasis to the Holy Spirit.

Jungmann refers to Vagaggini’s famous book, Il senso teologico della liturgia to reinforce his argument. What we have here, says Jungmann, is the personal theology of the author, not the universal theology of the Church. …

Verken Jungmann eller Bouyer (jeg har nettopp lest dem begge) er enige i at det er noen strukturelle eller innholdsmessige problemer med første eukaristiske bønn – tvert imot, Bouyer har ikke annet enn godt å si om den. Og P. Folsom er nok en forsiktig mann, for det eneste han foreslår at man skal gjøre med denne situasjonen, er som prester å bruke første eukaristiske bønn oftere.

Som vi leste i Aftenposten i går – og jeg nevnte her – jobber ikke politiet i Oslo med anmeldelsen mot OKB for øyeblikket. Det fikk sjefredaktør Simonnes i VL til å skrive på Verdidebatt:

Provoserende sent av politiet i Oslo

Oslo-politiet må få beskjed om at etterforskningen av Oslo katolske bispedømme ikke kan trekkes ut i langdrag.

Det er ikke hverdagskost at et trossamfunn og deres ledere blir siktet for grovt bedrageri i mange millioners-klassen. Saken har skapt voldsom furore i Oslo katolske bispedømme

Det er tusenvis av medlemmer som opplever å være berørt. Ledelsen i Oslo-politiet ser ikke ut til å forstå hva det betyr for et trossamfunn å ha en slik anklage hengende over seg.

Ifølge Aftenposten har politiet i Oslo i høst nedprioritert etterforskningen i saken der Oslo katolske bispedømme er siktet for å ha jukset med medlemslister. I vår lå også saken urørt i flere uker. Det er nå usikkert om en eventuell tiltalebeslutning vil foreligge før jul, slik politiet har signalisert tidligere. ….

På en måte er jeg enig – i alle fall i at myndighetene behandler oss ganske dårlig når det gjelder denne støtten/ skatterefusjonen – men jeg tillot meg likevel å skrive dette svaret til Simonnes:

Er det ikke heller departement og regjering vi venter på?

Men kanskje denne sendrektigheten fra politiet kan forstås på en litt annen måte:

Ved å si at Fylkesmannen i Oslo og Akershus dummet seg ut da de i februar politianmeldte Oslo katolske bispedømme før saken var grundig nok utredet. Det skrev tidligere sivilombudsmann Fliflet ganske tydelig i et vedlegg OKB i august la ved sin anke til Fylkesmann og departement. Politiet vurderte heller ikke denne saken grundig nok før de gikk til en helt unødvendig dramatisk aksjon.

Nå i høst har de norske styresmaktene for alvor begynt å vurdere om (det nye) kravet om aktiv innmelding i trossamfunn virkelig kan opprettholdes – representanter for de nordiske folkekirkene er i høst blitt innkalt til samtaler med Fylkesmannen, siden de i flere år har hatt en praksis lignende OKB. Så langt vet ingen hva konklusjonene vil bli – for katolikkene eller de nordiske folkekirkene.

Så hvordan kan politiet vurdere en anmeldelse når det er full forvirring om det som er gjort – å melde personer inn i trossamfunn uten deres aktive medvirkning – er lovlig eller strengt forbudt? Det kan være at politiet nedprioriterer saken fordi de ikke vet hvordan de skal håndtere den. Men jeg er enig i at det hadde vært mye bedre at de hadde sagt rett ut hva de tenker.

Og til slutt: Det er egentlig statsmakten, departement og regjering, som kan løse denne saken for katolikkene i Norge. Deres svar vil avgjøre om vi skal måtte gi fra oss 20 eller 105 millioner i stat- og kommunestøtte – som jeg har skrevet om her – og det er de som egentlig bestemmer hvordan denne politianmeldelsen skal avgjøres.

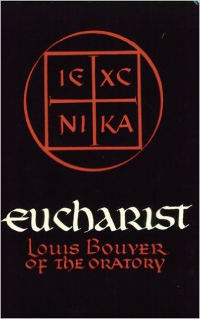

Jeg leste i dag ferdig Boyers bok EUCHARIST, der han tydelig skriver hvordan eukaristien best bør forstås; som en ihukommelse og takksigelse for Mirabilia Dei, Guds store frelseshandlinger. Det blir feil (skriver han) å fokusere på takken for den hellige kommunion (den kommer mer som et resultat av vår takksigelse for Guds store gjerninger og Kristi tilstedeværelse) og heller ikke på fellesskapsmåltidet (som også er et resultat av det samme). Helt på slutten av boka skriver han mye godt om den (nye, han skrev boka i 1968) tredje eukaristiske bønn (som er bygget på den galliske/spanske tradisjonen, men den andre eukaristiske bønn har han lite godt å si om; den er bygget på Hippolyts bønn, som (sier han) helt sikkert ikke har noe med den gamle romerske liturgien å gjøre. Forhåpentligvis vil jeg kunne klare å samle meg til å skrive litt mer om denne boka.

Jeg leste også i dag et intervju med Dr. Keith Lemna: Rev. Louis Bouyer: A Theological Giant – Dr. Lemna har studert Boyers bøker svært grundig, og i intervjuet sier han bl.a.:

Who was Fr. Louis Bouyer?

Dr. Lemna: Louis Bouyer was a priest of the Oratory, a convert to Catholicism from Lutheranism, which he had served as a minister, an eminent liturgiologist and historian of spirituality, an influential scholar of Newman (whose studies of Newman helped to pave the way for Newman’s eventual beatification), and, perhaps most importantly of all, one of the greatest Catholic theologians of the twentieth century.

What were some of Fr. Bouyer’s significant contributions in the realm of Catholic theology?

Dr. Lemna: Fr. Bouyer is known most of all as a scholar of liturgy and spirituality, and it is in these areas that his work has exercised its most overt impact on the course of Catholic theology as a whole. In the area of liturgy, Bouyer, himself drawing on the work of Dom Odo Casel, is the figure who is most responsible for the emphasis that has been placed in recent decades on the theme of the «Paschal Mystery» as central for understanding the mystery of the faith, and he, as much or more than anyone, oriented sacramental theologians to a focus on the liturgical event as the basis for theological reflection on the nature and meaning of the sacraments.

What were some of his key works?

Dr. Lemna: … Similarly important is his book on the Eucharist, Eucharistie, one of three seminal studies of Christian liturgy done in the twentieth century (along with Josef A. Jungmann’s The Mass of the Roman Rite, and Dom Gregory Dix’s The Shape of the Liturgy). In this book, Bouyer explores the theology and historical development of the Church’s Eucharistic prayer. He argues for the importance of developing a theology of the Eucharist based on attention to the act of the liturgy, rather than a theology about the Eucharist that takes its starting point in abstract metaphysical concepts that are then applied to the reality of the Eucharist. He shows the roots of the Christian Eucharist in Jewish Temple and synagogue practices, going beyond Casel’s thesis that the Church had borrowed its liturgical forms from the Greco-Roman mystery cults.

What influence did his work have on the Second Vatican Council?

Dr. Lemna: It is difficult to assess the precise influence that Bouyer’s work had on the council. By the time that the council had convened, many of Bouyer’s ideas had become common currency among some of the theologians who were present at the council, even if they were not influenced by Bouyer. Bouyer was a theological expert relied upon by the Church in the period surrounding the council, and he was greatly trusted by Paul VI, who appointed him to the first International Theological Commission after the council and who had wanted to name him a cardinal. Bouyer refused the offer, arguing that it would cause too much trouble for the Holy See. He had been engaged in fierce polemics with the later generation of liturgists in France, and his reputation had suffered as a result. …

What are some aspects of Fr. Bouyer’s work that are deserving of more study and consideration?

Dr. Lemna: … I think that the biggest obstacle to furthering his thought is that Bouyer wrote in a very polemical style at times, in a way that was off-putting to both «traditionalist» and «progressivist» camps in theology. But the old battles that fueled those polemics are largely a thing of the past by now, and most of the participants in those battles are dead. Bouyer could be equally sharp toward neo-Thomists, Rahnerians, and toward theologians influenced to a great extent by liberal Protestantism. …. Despite his penchant for polemics, his overall vision of the unity of Catholic doctrine, of the connection between theology and Christian life, and his unrivalled sense of the central importance of sacred liturgy for theology and for the existence of the Church stands out over and beyond all of the heated disputes. Cardinal Lustiger had said that Bouyer was perceived as «untimely» and «unwelcome» to the «very generations» to whom he was «providentially sent.» But perhaps in our time we can begin to see more clearly precisely how lucid and comprehensive—and, one might even say, «forward-looking»—was Bouyer’s vision of Catholic theology. …

I kveld leser jeg i Aftenposten at politiet har tatt en pause i etterforskningen av Oslo katolske bispedømme, etter at Fylkesmannen i Oslo og Akershus i februar anmeldte biskopen og økonomen i bispedømmet for bedrageri av 50 millioner kroner. Slik skirver de:

…Det er forøvrig bare én etterforsker som har jobbet med saken. Aftenposten får opplyst at hun «i noen uker» har vært flyttet over til en annen sak. Det understrekes at etterforskeren ikke er tatt av saken, og etterforskningsleder ved Finans- og miljøkrimseksjonen, Rune Skjold, sier at hun «forhåpentligvis er tilbake for å jobbe med den i løpet av desember».

«Jeg vil ikke spå noe tidspunkt for etterforskningsslutt», sier Skjold. …

«Vi er skuffet over at påtalemyndighetene ennå ikke har kommet med en konklusjon. Et helt bispedømme med over 130.000 medlemmer venter på hva som skjer i denne saken, og vi hadde håpet på en avklaring før jul. Det er en stor belastning å leve i en uavklart situasjon, og det er en stor belastning for alle involverte at denne saken drar ut i tid», skriver Wade. …

…OKB har gjennom flere redegjørelser hevdet at de ikke har gjort noe ulovlig. Kirken er uenig i at medlemskap krever «aktiv og uttrykkelig» innmelding eller bekreftelse, og mener det avgjørende er om de registrerte faktisk var katolikker da de ble registrert.

Det er selvsagt ubehagelig å måtte vente i måned etter måned på en avklaring. På den annen siden kan det være en fordel at man først får svar fra myndighetene og juridiske eksperter (event. domstolene) om det er nok at disse registrerte medlemmene virkelig er katolikker, eller om de i tillegg også må registrere seg ekstra og aktivt her i Norge. Da vil man få svar på om det er 10 eller 50 millioner statlige kroner OKB har mottatt for mye.

Lørdag ettermiddag gikk vi for å se på den store og berømte kirken San Lorenzo Fuori le Mura – som ligger litt utilgjengelig til bak Termini, utenfor den gamle bymuren. På vei dit gikk vi forbi Forum og kirken Santa Maria in Aracoeli – som jeg har sett flere ganger før, men ikke i år – så vi gikk innom en liten tur (se under).

Vi kom så til den hellige Laurentius’ kirke, og her viser jeg fem bilder, bl.a. av pave Pius IX, som etter eget ønske er gravlagt her.

På vei hjem utpå kvelden (etter pizza ikke langt fra Colosseum) gikk vi forbi Panteon, og så at Santa Maria sopra Minerva (der hl Katarina av Siena ligger under høyalteret) var åpen og orgelet spilte – der hadde jeg heller ikke vært innom før på denne turen.

Siden jeg nå for alvor begynner å lese p. Louis Bouyers bøker om liturgi (først med boken Eucharist), innser jeg at jeg nok burde ha gjort det tidligere. Jeg publiserer her innlegg på min blogg som jeg skrev for snart seks år siden, der det refereres til Bouyer og hans nokså karakteristiske jødiske synspunkter på teologien. Slik skrev jeg for seks år siden som innledning til et sitat: I John Baldovins bok (som jeg nevnte HER), som i utgangspunktet er kritisk til kritikerne av den nye messen, men som gjengir disse kritikernes synspunkter ganske så presist, er det også en beskrivelse av pave Benedikts/ kardinal Ratzingers synspunkter på liturgiforandringene, bl.a. dette:

Of all the liturgical questions on which he has written, Cardinal Ratzinger has clearly created the most stir with his attitude toward the orientation of the priest-celebrant at Mass … To understand the stance he has taken, one must appreciate his theory of the development of church architecture. Basically he has accepted the theories put forward by Louis Bouyer in his famous Liturgy and Architecture. Bouyer argued a direct link between the architecture of Jewish synagogues and the development of Christian church buildings, with the latter oriented toward the east instead of toward Jerusalem. In place of the ark containing the Torah, Christians set up the cross of Christ. Ratzinger sees in the «orientation» (literally east-facing) of Christian churches an attitude of eschatological expectation. The cross symbolizes the returning Christ, who will rise like the sun. Thus the priest in offering the sacrifice faced east and the altar was placed near the eastern apse of the church building. Ratzinger emphatically insists that in the early church it was never a question of «facing the people» (versus populum) or not but rather one of orientation. …

For Ratzinger the position of the altar is «at the center of the postconciliar debate.» Having the priest face the people has caused a fundamental shift, essentially a novelty, in the meaning of the liturgy which now looks like a communal meal.» As we have seen above, he rejects this as a one-sided interpretation that fails to take the sacrifice aspect of the liturgy into account. To make matters worse, the liturgy now becomes primarily a matter of roles, since the priest’s role has been so greatly accentuated and others need to have their functions too. The problem with all this for Ratzinger is that the liturgy devolves info a «self-enclosed circle» rather than worship directed toward God. There is some accuracy to his criticism of a liturgy that has focused more and more on the role-and personality of the priest. The great irony here is that in the pre-Vatican II liturgy the priest was not all that important (except when he sang badly). The «success» of the liturgy had little to do with his personality, except for the fact that people might prefer the piety and devotion of one priest over another. Now, I would agree, too much can depend on the personality of the priest, who must exercise enormous self-discipline in not succumbing to the temptation to put himself forward.

In his reply to Pierre-Marie Gy, Ratzinger has recently reiterated that he does not necessarily want a return to the eastward position. He regards his own stance as rather nuanced. It involves three factors:

1. He thinks there should be a separate space for the proclamation of the Word.

2. In large churches where the apse altar is a great distance from the people, an altar should be constructed closer to them.

3. Altars need not be «turned around» again. Instead, the «liturgical East» can be symbolized by a cross in the center of the altar toward which both priest and people face.

He puts the last point this way: «To be able to fix our gaze, all of us together, on him who is the Creator, the one who receives US into the cosmic liturgy, and who shows us also the path of history; this is what would enable us to recover the dimension of deep unity that exists between the priest and the faithful within their common priesthood.” Elsewhere he had already regarded moving the cross on the altar to one side an absurd phenomenon in the liturgical reform. I think it is fair to say, however, that he wishes that the altars had never been «turned around.»

Jeg begynner nå å lese p Louis Louis Bouyers bok EUCHARIST, der han i løpet av nesten 500 sider går gjennom utviklingen og forståelsen av messen. Bouyers stil er veldig annerledes enn Jungmanns, som var svært saklig og lite kritisk kommenterende til andre forskeres bidrag. Bouyer har en ganske annen kontroversiell og aktuell stil. Slik begynner han f.eks. forordet, som han skrev i juni 1966 og januar 1968 (2. utgave):

Jeg begynner nå å lese p Louis Louis Bouyers bok EUCHARIST, der han i løpet av nesten 500 sider går gjennom utviklingen og forståelsen av messen. Bouyers stil er veldig annerledes enn Jungmanns, som var svært saklig og lite kritisk kommenterende til andre forskeres bidrag. Bouyer har en ganske annen kontroversiell og aktuell stil. Slik begynner han f.eks. forordet, som han skrev i juni 1966 og januar 1968 (2. utgave):

This book is the result of more than twenty years of research. It is appearing at a moment when the understanding of the traditional Eucharistic prayer, and especially the canon of the Roman mass, is more timely than ever. On one hand it has been a very long time since we have seen such lively and widespread desire in the Catholic Church to rediscover a “eucharist” that is fully living and real. Yet, unfortunately, there has also never been a time when we have been so confidently presented with such fantastic theories that, once put into practice, would make us lose practically everything of authentic tradition that we have still preserved. May this volume contribute its part towards promoting this renewal and discouraging an ignorant and pretentious anarchy that could mean its downfall. …

I 1968 har messen og holdningene til den allerede forandret seg en del, og på s 10 skriver Bouyer ganske skarpt om resultatet av enkelte forandringer:

… we may congratulate ourselves on our discovery of the collective sense of the eucharistic celebration through a return to notions of the eucharistic sacrifice that imply our own participation. But it is already a very bad sign that the values of adoration and contemplation, which yesterday focused on a eucharistic devotion that was in fact foreign to the eucharist, seem hardly to have come back to our celebration of it, but have rather simply vanished into thin air …

Han referer her til at eukaristisk tilbedelse (utenom messen) ikke er en særlig sentral praksis, i forhold til selve messefeiringen, selve frembæringen av messens offer. Men når man motarbeider gamle, fromme tradisjoner, uten å erstatte dem med noe nytt, blir jo resultatet ganske katastrofalt.

Avisa Dagen skriver i dag i en lederartikkel om reaksjonen da de leste boka «Den stora upptäckten»: «For de av oss som hører til på den evangeliske side av kristenheten er boken utfordrende og til dels smertefull lesning.» Og de skriver også:

… Ulf Ekman skriver at konverteringen for dem var «et sannhetsspørsmål og ikke bare handlet om en spesiell vei som akkurat vi skulle gå». Han understreker gang på gang at han tror på hele Den katolske kirkes lære. Også de utenombibelske dogmene om Maria, om helgenene, om skjærsilden, paveembetet og så videre. Store deler av boken er faktisk en gjennomgang av hvordan ekteparet Ekman nærmet seg de ulike katolske læresetningene. Og sakte, men sikkert gjorde dem til sine egne. …

For de av oss som hører til på den evangeliske side av kristenheten er boken utfordrende og til dels smertefull lesning. Uansett om det er ment slik eller ikke, fungerer den nemlig i praksis langt på vei som et angrep på evangelisk tro og de protestantiske grunnsannheter. …

… I «Den stora upptäckten» argumenterer han mot det han tidligere kjempet så sterkt for. Blant annet det helt sentrale reformatoriske prinsippet «Skriften alene». Den læresetningen får nå av Ekman merkelappen «ubibelsk». I stedet argumenter han for at Bibelen «kan ikke leses isolert fra Tradisjonen, det vil si Kirkens samlede og av Ånden ledede muntlige undervisning og erfaring». …

Jeg har aldri vært noen tilhenger av teologien og gudstjenestepraksisen hos Livets Ord, tvert imot, tidlig på 90-tallet var jeg aktiv i en gruppe som prøvde å hjelpe avhoppere fra denne og lignende menigheter. Likevel får jeg lite sympati for fjernsynsprogrammet Uppdrag Granskning, som i går hadde en reportasje om økonomien i Livets Ord, og til Ulf Ekman, (mest) på 80- og 90-tallet. Vårt Land refererer til dette programmet (nokså ukritisk), mens Livets Ord selv (og menigheten er nok i dag ganske ulik det den var på 90-tallet) svarer konkret på mange av anklagene som ble presentert – at flere av anklagene er feil, og at programmet et svært ensidig og urettferdig, nærmest uredelig. Se mange konkrete svar her, og her et uklippet intervju med dagens forstander. Og om Ulf Ekman sier forstander Joakim Lundqvist:

Ulf är inte längre en del av vår rörelse, men under de år han var det lärde vi känna honom som en generös och engagerad människa med stort hjärta både för Livets Ord och vårt arbete.

Till Ulfs försvar ska sägas att han under sina år som pastor tog ut en mycket modest månadslön och ofta avstod den helt i tider av ekonomiska utmaningar. I vår dokumentation av gåvor till arbetet genom åren finns Ulf själv ständigt med bland de mest generösa givarna.

Genom vår historia finns det saker som hade genomförts på ett annorlunda sätt idag, men att påstå att Ulf skulle ha utnyttjat människors godtrogenhet för att samla sig privata rikedomar är en felaktig och djupt orättvis beskyllning.

OPPDATERING:

Jeg leser nå at Ulf Ekman selv har skrevet om dette på sin blogg.

OPPATERING 2:

Norske Dagen skriver litt utpå dagen en hel del om denne saken

Pave Benedikt var meget imøtekommende mot anglikanere som ønsket å bli katolikker samtidig som de ville beholde noe av sin spesielle anglikanske, liturgiske arv, og han opprettet Ordinariatet for dem i 2009. De har hatt dyktige ledere for arbeidet siden starten, men disse har ikke vært bispeviet siden de er gifte menn. Nå får Ordinariatet i USA sin første biskop, og John Allen skriver at dette også viser at pave Benedikt og pave Frans har mer felles enn mange tror:

At the level of style, Pope Francis is obviously a somewhat jarring contrast with his predecessor, emeritus Pope Benedict XVI. Francis generally comes off as a warm Latin populist, Benedict more a cool German intellectual.

Leaders, however, promote either continuity or rupture not primarily at the level of style but rather policy, and on that front, one can make a case that Francis has a surprising amount in common with Benedict. His reforms on both Vatican finances and the clerical sexual abuse scandals, to take one example, are clearly extensions of Benedict’s legacy.

A new chapter in this largely untold story of continuity came on Tuesday, when the pontiff tapped 40-year-old American Monsignor Steven Lopes as the first-ever bishop of the Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter, one of three jurisdictions created under Pope Benedict in 2012 to welcome former Anglicans into the Catholic Church. …

… In a Crux interview Wednesday, Lopes said he sees his new job as all about continuity between the two popes. “I worked very closely with Pope Benedict in creating the ordinariates, and I know his vision was of allowing diversity in communion,” he said. “Pope Francis embraces that model and is pushing it through to its logical conclusion.”

Francis, Lopes said, is conscious of carrying forward his predecessor’s approach. “I met with Pope Francis last Wednesday and heard from him on this very point,” Lopes said. “He knows very well what he’s doing.” …

… At the moment, Lopes said, the ordinariate for the United States and Canada has 42 parishes, 64 priests, four deacons, and roughly 20,000 faithful. It’s in an expansion phase, he said, both because other Anglican communities are still requesting entrance, and because his parishes tend to be keenly missionary and are attracting new members. …

I siste nummer av St Olav kirkeblad – som kan leses her, flere nummer av tidsskriftet finner man her – kan man lese om vanskelige medlemsregisteringssaken/ politianmeldelsen, skrevet av fungerende administasjonssjef Lisa Wade, bl.a:

OKB, biskopen og vår økonom ble siktet for grovt bedrageri. Det føltes absurd da – og det føles absurd nå. Vi levde i en kirke som vokste raskt, systemer og prosesser klarte ikke å holde tritt, og det ble valgt mindre gode løsninger for å registrere nye medlemmer. Uheldig, ja. Men grovt bedrageri?

En siktelse er et foreløpig uttrykk for at politiet har mistanke om at det er begått straffbare handlinger. Det er et grønt lys for at politiet kan undersøke om bestemte personer/rettssubjekter kan ha gjort seg skyldig i straffbare forhold. Loven sier ingenting om hvor lang tid politiet kan bruke på denne jobben – eller hvordan de siktede skal holdes informert.

Gjennom media har vi fått vite at påtalemyndighetene håper å konkludere før jul. Vi vet også at saken er løftet opp på statsadvokatnivå. Det kan bety at saken regnes som særskilt viktig eller komplisert.

Hvis påtalemyndighetene konkluderer med at OKB, vår biskop eller vår økonom har «hatt et bevisst ønske om uberettiget vinning» og gjort seg skyldig i grovt bedrageri, tas det ut tiltale og saken kommer for retten. Det andre alternativet er at saken henlegges, enten på grunn av «intet straffbart forhold» eller «på grunn av bevisets stilling».

Administrasjonen har vært og er fremdeles optimister med hensyn til straffesaken. Vi tror ikke noen av våre medarbeidere har gjort noe straffbart. Likevel, månedene går og ventetiden er tung – ikke bare for de direkte involverte, men for alle katolikker i Norge. Vi er en preget Kirke og et felleskap med en klump i magen. Men vi er langt fra lammet. … …

Vårt Land bruker dette bildet til å illustrere ulike former for gudstjenesteliv i Den norske kirke, og det er fra Uranienborg kirke i Oslo – artikkelen ble publisert i fjor, men de lenker til den i dag. For en katolikk er det underlig – og spesielt for meg, som akkurat nå leser om den katolske messeliturgien gjennom tidene – å kunne observere at det nesten alle steder i verden (og absolutt alle steder i Norge) ville være uaktuelt å bruke en kirke som ser så høytidelig ut. For: korpartiet er trukket et ganske langt stykke bort fra folket, det er en skjerm som deler av koret, man har et alter som er vendt bort fra folket, man har en alterring der folk kneler når de mottar nattverd/ kommunion – og til og med en nokså høy prekestol. I Norge ble kirker som så slik ut modernisert på 70-tallet, og nye kirker ble bygget med et frittstående bordalter, og uten kommunionsbenk og prekestol. Det er egentlig ganske sjokkerende at katolikkene oppførte seg så misforstått moderne.

Jeg liker riktignok heller ikke selv alle gamle kirkerom, og avstanden mellom folket og presten/ alteret opplever jeg som ganske viktig. I en full kirke er en forholdsvis stor avstand naturlig, i en messe med bare noen få til stede er stor avstand ganske ubehagelig – syns jeg. Eamon Duffy skiver om katolsk kirkeliv i England rundt 1500, at i søndagens høymesse ble høyalteret – som var trukket en godt stykke tilbake inn i et kor delt av med en skjerm – alltid brukt, men også her var det ganske mye kontakt mellom den store folkemengden i kirkerommet og presten; ved prosesjonen gjennom kirkerommet og stenkingen med vievann i starten av messen, ved preken, forbønner, kunngjøringer, der presten stod godt synlig for menigheten (og snakket engelsk), da alle kom fram og kysset «pax-bredet» (som fredshilsen), når folk (av og til) mottok kommunion, og ved utdelingen av velsignet brød etter messen (den tradisjonen hadde holdt seg). Ved ukedagsmessene var situasjonen en helt annen, skriver Duffy, da brukte man sidealterne (og messene ble gjerne feiret for en avdød, eller for en av de mange foreningene som fantes i menigheten) og folk stod helt inntil presten mens han feiret messen.

I England var også skjermene foran koret svært viktige i nesten alle kirker. De kalles rood screen, der rood betyr krusifiks, som stod på toppen av skjermen (se bildet under). Ved reformasjonen ble krusifiksene revet ned, men skjermene ble ofte stående (om de ikke hadde for mange helgenbilder). Les om rood screens på Wikipedia her.