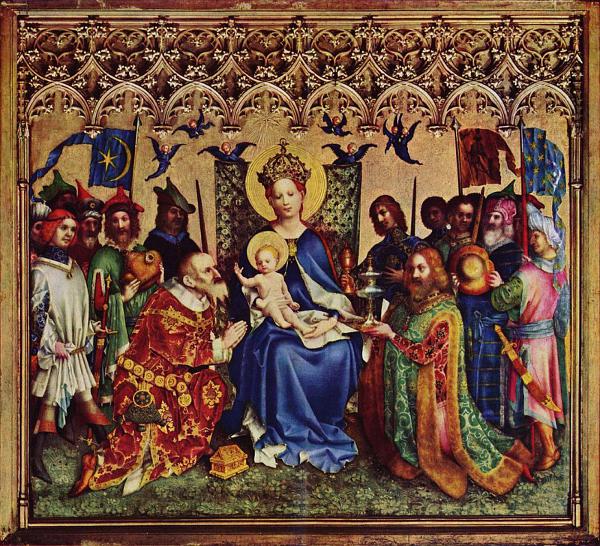

Kongenes tilbedelse – Kølnerdomen

Kongenes tilbedelse (c. 1440), Stefan Lochner (ca. 1400-1451) Bildet danner midtpartiet i et triptykon i Mariakapellet i Kölnerdomen.

Les mer om dette alterbildet – og om hele Kølnerdomen (begge artikler på tysk),

Kongenes tilbedelse (c. 1440), Stefan Lochner (ca. 1400-1451) Bildet danner midtpartiet i et triptykon i Mariakapellet i Kölnerdomen.

Les mer om dette alterbildet – og om hele Kølnerdomen (begge artikler på tysk),

Jeg har startet på et ganske stort verk (650 s), om katolske liturgier (både messen og andre liturgier, dåp, konfirmasjon etc) i middelalderen: A Sense of the Sacred: Roman Catholic Worship in the Middle Ages, av James Monti.

Jeg har startet på et ganske stort verk (650 s), om katolske liturgier (både messen og andre liturgier, dåp, konfirmasjon etc) i middelalderen: A Sense of the Sacred: Roman Catholic Worship in the Middle Ages, av James Monti.

Ignatius press presenterer boka slik:

This incomparable volume presents a comprehensive exploration and explanation of medieval liturgical celebrations. The reverent prayers, hymns and rubrics used in the Middle Ages are described in detail and interpreted through the commentary of scholars from the same time period, the era which is also known as the «Age of Faith».

Collected here is a wide range of ceremonies, encompassing the seven sacraments, the major feasts of the liturgical year (such as Christmas, Easter, and Corpus Christi), and special liturgical rites (from the coronation of the pope to the blessing of expectant mothers). The sacred celebrations have been drawn from countries across western and central Europe-from Portugal to Poland-but particular attention has been given to liturgical texts of medieval Spain, which until now have received relatively little attention from scholars.

Historian James Monti has done exhaustive research on medieval liturgical manuscripts, early printed missals, and the writings of medieval liturgists and theologians so that the treasures they contain can inspire a sense of the sacred in future generations of Catholics.

Et par anmeldere sier om boka:

«James Monti’s treatise is an astonishing achievement, a book that can and will shape a new generation of intellectuals who are serious about the Catholic liturgy. Despite the title, this book is not only about medieval liturgy. It’s about inspiring the creation of, and the provision of access to, truly sacred spaces in our time, even in a world that seems so barren of them. My own special interest is in Gregorian chant, but Monti’s book helps broaden the picture to include a spiritual panorama of extraordinary breadth and depth. We have so much to learn from the past and so much to work toward for a bright and beautiful future of recaptured truth.»

«Among the ambiguous legacy of the Liturgical Movement of the twentieth century is the neglect and incomprehension of medieval liturgy. This book is a welcome contribution towards redressing this imbalance. James Monti recovers the tradition of mystical commentary on the sacred rites, a common heritage of East and West, and enriches it with his vast historical erudition. This volume will serve as a useful resource for anyone who wishes to enter into the spirit of the liturgy that shaped a millennium of Christian history.»

De to bøkene jeg nettopp har lest av Lang er The Voice of the Church at Prayer: Reflections on Liturgy and Language og Signs of the Holy One: Liturgy, Ritual, and Expression of the Sacred. To gode bøker, men det er nokså korte (og for det meste enkle), så det var ikke så mye ny informasjon for meg i dem.

De to bøkene jeg nettopp har lest av Lang er The Voice of the Church at Prayer: Reflections on Liturgy and Language og Signs of the Holy One: Liturgy, Ritual, and Expression of the Sacred. To gode bøker, men det er nokså korte (og for det meste enkle), så det var ikke så mye ny informasjon for meg i dem.

Den første boka beskrives slik hos ignatius.com:

Pope Benedict XVI has made the liturgy a central theme of his pontificate, and he has paid special attention to the vitally important role of language in prayer. This historical and theological study of the changing role of Latin in the Roman Catholic Church sheds light on some of the Holy Father’s concerns and some of his recent decisions about the liturgy.

The Fathers of the Second Vatican Council allowed for extended use of the vernacular at Mass, but they maintained that Latin deserved pride of place in the Roman Rite. The outcome, however, was that modern translations of the prayers of the Mass replaced the Latin prayers.

What was the reason for the Council’s decision and why is there now a desire for greater use of Latin in Catholic worship? Why have some post-conciliar English translations of the prayers of the Mass been replaced?

Fr. Lang answers these questions by first analyzing the nature of sacred language. He then traces the beginnings of Christian prayer to the Scriptures and the Greek spoken at the time of the apostles. Next he recounts the slow and gradual development of Latin into the sacred language of the Western Church and its continuing use throughout the Middle Ages. Finally, he addresses the rise of modern languages and the ongoing question of whether the participation of the laity at Mass is either helped or hindered by the use of Latin.

Den andre boka er beskrevet slik:

Catholic liturgy is far more than its texts. It is a synthesis that also includes several other elements—gesture, music, art, and architecture—which are aspects of the non-verbal language of the sacred and are what make the liturgy beautiful.

Father Lang’s consideration of the beauty of the liturgy addresses the modern notion that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, that the experience of beauty is entirely subjective. This idea makes it difficult to articulate criteria for what is beautiful, yet sacred liturgy does indeed have objective measures for evaluating its principal elements. Reflecting upon these and quoting from authoritative Church documents, Father Lang discusses sacred music, art, and architecture, and demonstrates how the beauty of these elements makes present the sacred.

Pope Benedict XVI said, “The greatness of the liturgy depends—we shall have to repeat this frequently—on its non-spontaneity.” Continuous liturgical experimentation is unable to induce a sense of meaning or peace, writes Father Lang, because novelty does not satisfy the yearning for the Transcendent within the human psyche, which is rarely far from the surface.

Jeg har nå lest ferdig ei bok jeg må innrømme at jeg ikke likte noe særlig. Det er Sacrifice Unveiled, The True Meaning of Christian Sarifice, skrevet av Robert Daly, SJ. Boka ble utgitt i 2009 men forfatteren har visst arbeidet med offer-temaet siden 60-tallet, og visst oppdaget mye nytt via fenomenoligiske og mimetiske teorier, og en grunnleggende forståelse av at offeret (og eukaristien) er Trinitarisk (hva nå det skal bety). I praksis fører det til at det er lite igjen av katolske forståelse av Kristi offer, og av eukaristien.

Jeg har nå lest ferdig ei bok jeg må innrømme at jeg ikke likte noe særlig. Det er Sacrifice Unveiled, The True Meaning of Christian Sarifice, skrevet av Robert Daly, SJ. Boka ble utgitt i 2009 men forfatteren har visst arbeidet med offer-temaet siden 60-tallet, og visst oppdaget mye nytt via fenomenoligiske og mimetiske teorier, og en grunnleggende forståelse av at offeret (og eukaristien) er Trinitarisk (hva nå det skal bety). I praksis fører det til at det er lite igjen av katolske forståelse av Kristi offer, og av eukaristien.

Daly har også skrevet en kortere framstilling av det boka handler om, og derfra siterer jeg:

… Traditional Western atonement theory — at least in its extreme, but all-too common forms — ultimately reduces to something like the following caricature: (1) God’s honor is damaged by sin; (2) God demanded a bloody victim to pay for this sin; (3) God is assuaged by the victim; (4) the death of Jesus the victim functioned as a payoff that purchased salvation for us.

Such a theory is literally monstrous in some of its implications. For when it is absolutized or pushed to its “theo-logical” conclusions and made to replace the Incarnation as central Christian doctrine, it tends to veil from human view (from Protestants as well as from Catholics) the merciful and loving God of biblical revelation. Despite my books and articles on the subject, I had for many years no satisfactory answer to this problem.

That changed when, serendipitously forced to edit Ed Kilmartin’s last book, I discovered the trinitarian understanding of sacrifice to which I now turn. Authentic Christian, that is, Trinitarian Understanding of Sacrifice Constantly fine-tuning my own understanding of it, … First of all, Christian sacrifice is not some object that we manipulate; it is not primarily a ceremony or ritual; nor is it something that we “do” or “give up.” For it is, first and foremost, something deeply personal: a mutually self-giving event that takes place between persons. Actually it is the most profoundly personal and interpersonal act of which a human being is capable or in which a human being can participate.

It begins in a kind of first “moment,” not with us but with the self-offering of God the Father in the gift-sending of the Son. Christian sacrifice continues its “process of becoming” in a second “moment,” in the self-offering “response” of the Son, in his humanity and in the power of the Holy Spirit, to the Father and for us. Christian sacrifice continues its coming-to-be, and only then does it begin to become Christian sacrifice in our lives when we, in human actions that are empowered by the same Spirit that was in Jesus, begin to enter into that perfect, en-spirited, mutually self-giving, mutually self-communicating personal relationship that is the life of the Blessed Trinity. …..

På øverste bilde har jeg nettopp kommet opp fra årets første bad, 1/1 kl 12.00! Den ganske berømte Amadores-stranda ligger rett nedenfor vår leilighet. Det andre bildet viser utsikten fra vår balkong ved solnedgang, Tenerife i bakgrunnen.

Jeg leste mesteparten av boka Sacrificed Unveiled, av Robert Daly, SJ, i dag og har lite godt å si om den. Kommer tilbake med mer stoff om dette om ikke lenge.

Det tredje eksempelet fra artikkelen jeg allerede har vist til, er biskop Edward Slattery i Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA. Han sier at han nesten alltid når han feirer messe i sin domkirke (de siste fem år) har han feiret messen «vendt samme vei som folket». Vider kan vi lese:

Bishop Slattery sees Cardinal Sarah’s recent liturgical remarks as a continuation of what Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger taught, especially in The Spirit of the Liturgy, while serving as prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith prior to his election as Pope Benedict XVI. This, in turn, is seen by Bishop Slattery as a continuation of what the Fathers of Vatican II taught: “It’s nothing new, really. It’s not only a decades-old tradition, but a centuries-old tradition of the Church that has solid theological and practical foundations.”

It is common sense to Bishop Slattery, who recalls simple rules of communication: “When I’m speaking to someone, I usually face that person. So when I’m giving a sermon, I face the people, because they are the ones I’m addressing. When I’m in prayer — especially offering Jesus to the Father at the altar — I’m addressing the Father, so it is no wonder that I should be facing him, rather than the people.”

Bishop Slattery believes authentic participation is not facilitated by the priest facing the people at these times, because then the priest becomes the central focus … “The priest is supposed to lead the people in Christ to the Father,” the bishop added, “yet when the priest faces the people, he becomes a locked — rather than an open — door. Instead of thinking about Christ going to the Father, the faithful are thinking about the personality of the priest.”

Kardinal Robert Sarah er prefekt for Liturgikongregasjonen i Vatikanet, og skrev i juni i år om alterets og prestens retning i kirkerommet. Vatikankonsilet sa ikke noe om at alteret skulle snus, og faktisk er bedre at presten ikke har en så dominerende rolle i messen at han står og sitter rett foran menigheten, og vender seg mot dem under hele messen. Slik omtales det han skriver:

… The topic drawing most attention in the article was the direction of liturgical prayer — specifically, how the priest and people should be facing the same way during many parts of the Mass.

While some see this as a return to a “pre-Vatican II” liturgy, Cardinal Sarah showed it is quite the opposite — that it is, in fact, consonant with conciliar teachings. …. The African cardinal explained that “it is in full conformity with the conciliar constitution — indeed, it is entirely fitting — for everyone, priest and congregation, to turn together to the east during the penitential rite, the singing of the Gloria, the orations and the Eucharistic Prayer, in order to express the desire to participate in the work of worship and redemption accomplished by Christ.”

Cardinal Sarah emphasized that the priest must become the “instrument that allows Christ to shine through.” In the pursuit of this goal, he references Pope Francis remarking that the celebrant is not the host of a show, nor should he be seeking affirmation from the congregation, as if the primary concern of worship were a dialogue between the priest and assembly.

On the contrary, Cardinal Sarah believes that in order to enter into the true conciliar spirit, self-effacement is necessary for the priest who leads public worship. This self-effacement is implicit in the rubrics of the Roman Missal, which presume the priest will not be facing the congregation through the entirety of the Mass.

Dette har jeg tatt fra samme artikkel som jeg nevnte i går.

Jeg reiser ganske snart til utlandet igjen, og vil fortsette å lese om liturgiens utvikling – mest fram til ca år 1600, men jeg ser også på enkelte nyere temaer. Ett av disse helt nye temaene er hvilken vei presten og alteret skal vende seg under under messen – eller mer presis under deler av messen, for presten bør jo vende seg jo mot menighetslemmene når han snakker til dem. Jeg ser nå litt på hvorfor den liturgiske bevegelsen etter hvert (kanskje rundt 1930) begynte å tenke på å «snu alterne», noe vel ingen hadde tenkt på på langt over 1000 år (og knapt nok før den tid).

Jeg kom over denne artikkelen som tar opp dette temaet. En prest i Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA, har i sin menighet flyttet alteret tilbake til den opprinnelige plassen, undervist menigheten om dette, og om dette kan vi lese i artikkelen:

This traditional direction of liturgical prayer, referred to as ad orientem (facing east), had been nearly ubiquitous before the Second Vatican Council, yet almost vanished after it. This left most Catholics feeling the Council called for the priest to face the congregation, yet this was just that — a feeling — rather than a correct perception. None of the 16 conciliar documents contains an endorsement, let alone a mention, of the practice of the priest facing the congregation (versus populum) during the prayers of the Mass.

When Father Gawronski points this out to parishioners, he finds them to be generally receptive to it. “Old St. Patrick’s” worshippers have found his ad orientem Masses to be coherent and meaningful expressions of prayer. Rather than thinking of Father Gawronski as “having his back to the people,” parishioners see his positioning as the Church intends, expressive of the unity of the priest and congregation in their quest for God.

Father Gawronski believes the whole point of ad orientem worship is to demonstrate that the entire community is on the same page by facing the same God in prayer. …

Denne søndagen feires søndag i juleoktaven etter den tradisjonelle kalenderen, i St Hallvard kirkes kapell kl 08.00.

Søndagens inngangsvers ser slik ut: «Mens dyp taushet lå over alle ting og natten var rukket midtveis i sitt løp. kom ditt allmektige Ord, Herre, ned fra den himmelske kongsstol. Herren er Konge, han har kledd seg i herlighet; han har ikledd seg styrke, og omgjordet seg. »

Og julepresfasjon (som brukes i denne messen) ser slik ut:

I sannhet verdig og rett er det, riktig og gagnlig at vi alltid og overalt takker deg, hellige Herre, allmektige Fader, evige Gud. For ved det menneskevordne Ords mysterium er det nye lys av din klarhet strålt fram for vår sjels øyne, så vi, når vi synlig erkjenner Gud, ved ham blir dradd til å elske det usynlige. Og derfor synger vi med engler og erkeengler, med troner og herredømmer og med hele den himmelske hærskare din herlighets pris, idet vi uten stans istemmer:

LES ALLE SØNDAGENS TEKSTER HER.

Neste TLM blir 31. januar (5. søndag i mnd). Da feires søndag sexagesima. Se oversikten her.

Jeg har lest ferdig Matthew Leverings bok Sacrifice and Community, som han avslutter på denne måten (inkludert et sentralt og interessant sitat fra pave Benedikt):

Jeg har lest ferdig Matthew Leverings bok Sacrifice and Community, som han avslutter på denne måten (inkludert et sentralt og interessant sitat fra pave Benedikt):

… As Dostoevsky writes, «And so, man must unceasingly feel suffering [because of man’s sin], which is compensated for by the heavenly joy of fulfilling the law, that is, by sacrifice.»

In exploring Eucharistic theology in this book, I have argued that such radical communion is attained most fully on earth in the Eucharist, which as our sacrificial sharing in Christ’s sacrifice provides a foretaste of the radical communion that is heaven. In the sacrifice-sacrament of the Eucharist, we learn charity by offering with Christ his own saving sacrifice. The sacrament of the Eucharist is a “school” of charity; it builds the Church by enabling us to enact Christ’s sacrifice with him. In the liturgy of the Eucharist, we learn “Jesus Christ and him sacrificed” and thereby we “put on the whole armor of God”. …

… All aspects – theological and liturgical – of the Eucharist should therefore express our Eucharistic sharing in Christ’s cruciform Godwardness, which deifies us. Joseph Ratzinger has described the opposite situation, in which the liturgy of the Eucharist, not understood “ecstatically” as a sacrifice, finds its ground in itself rather than in God:

“The turning of the priest toward the people has turned the community into a self-enclosed circle. In its outward form, it no longer opens out on what lies ahead and above, but is locked into itself. The common turning toward the East was not a «celebration toward the wall»; it did not mean that the priest «had his back to the people»: the priest himself was not regarded as so important. For just as the congregation in the synagogue looked together toward Jerusalem, so in the Christian Liturgy the congregation looked together «toward the Lord». As one of the fathers of Vatican II’s Constitution on the Liturgy, J. A. Jungmann, put it, it was much more a question of priest and people facing in the same direction, knowing that together they were in a procession toward the Lord. They did not close themselves into a circle, they did not gaze at one another, but as the pilgrim People of God they set off for the Oriens, for the Christ who comes to meet us.”

I would add that this “procession toward the Lord” advances only insofar as it is cruciform, that is to say insofar as the communion of the pilgrim People of God arises in and through Christ’s saving sacrifice and our Eucharistic (sacrificial) participation in it. …

Jeg har akkurat lest ferdig kapittel 2 i Matthew Leverings bok Sacrifice and Community (som jeg skrev om her), et kapittel han kaller The Eucharist and Expiatory Sacrifice. Her sier han først at reformert jødedom og noen moderne kristne teologer egentlig ikke ønsker å snakke om soning for synd i det hele tatt. Levering, derimot, siterer Aquinas og Paulus svært grundig og viser at og hvordan menneskenes synder måtte sones for Gud, og hvordan Kristi offer på korset gjorde akkurat dette. Deretter knytter han dette sonofferet til eukaristien, og viser hvordan dette offeret gjentas i messens hellige offer «not as a distinct oblation, but a commemoration of that sacrifice which Chist offered». Og så avslutter han kapittelet slik:

Jeg har akkurat lest ferdig kapittel 2 i Matthew Leverings bok Sacrifice and Community (som jeg skrev om her), et kapittel han kaller The Eucharist and Expiatory Sacrifice. Her sier han først at reformert jødedom og noen moderne kristne teologer egentlig ikke ønsker å snakke om soning for synd i det hele tatt. Levering, derimot, siterer Aquinas og Paulus svært grundig og viser at og hvordan menneskenes synder måtte sones for Gud, og hvordan Kristi offer på korset gjorde akkurat dette. Deretter knytter han dette sonofferet til eukaristien, og viser hvordan dette offeret gjentas i messens hellige offer «not as a distinct oblation, but a commemoration of that sacrifice which Chist offered». Og så avslutter han kapittelet slik:

… avoiding an idealist account of the Eucharist does require recognizing as the fulfillment of the «practice of Israel,» the expiatory character of Christ’s sacrifice within the created order constituted by relationships of justice. The Eucharist as a sacramental-sacrificial participation in Christ’s expiatory sacrifice, configures and nourishes Christ’s mystical body … (p 94)

Jeg har, som jeg skrev i går, begynt å lese Matthew Leverings bok Sacrifice and Community: Jewish Offering and Christian Eucharist. Her skriver Levering om sakramental/eukaristisk realisme eller idealisme, og starter med å undersøke hvordan Det nye testamente og den første kristne liturgien bygger på jødenes forståelse og tempeltjeneste. Det er tydelig at levering selv har mer tro på en liturgisk realisme heller enn en idealisme; slik omtaler og siterer han den jødiske teologen Wyschogrod, som skrev slik på 90-tallet:

For Wyschogrod, to conceive of a communion with God outside such sacrifice is to fall into rationalism. He writes: “Above all, sacrifice is not an idea, but an act. Prayer and repentance are ideas. They are contemplative actions, of the heart rather than the body. For this reason, rationalists of all times have been delighted by the termination of the sacrifices. For them, the “service of the heart” is self-evidently more appropriate for communication between man and their rational God than the bloodbaths of a Temple-slaughterhouse.”

It follows that the communion, from our side, is only real if sacrificial. Sacrificial worship affirms that communal sacrifice is the only posture in which we can, as creatures, truly enter into communion with God. Wyschogrod states: “Enlightened religion recoils with horror from the thought of sacrifice, preferring a spotless house of worship filled with organ music and exquisitely polite behavior. …”

Non-sacrificial communion involves neither the human being’s true (completely dependent) self, nor God’s presence transforming and embracing the full human being.

Jeg begynner nå å lese boka Sacrifice and Community: Jewish Offering and Christian Eucharist, skrevet av professor Matthew Levering og utgitt i 2005. Starten på bok virker lovende; Levering viser når og hvordan også katolske teologer (Luther hadde allerede gjort det) begynte å hevde at eukaristien hadde lite med offer å gjøre. (Det er ett av temaene jeg gjerne vil finne mer ut om disse studiemånedene.) På amazon.co.uk omtales boka bl.a. slik:

This book explores the character of the Eucharist as communion in and through sacrifice. Drawing on Jewish reflection upon the Aqedah (the near–sacrifice of Isaac by Abraham in Genesis), as well as on other critical analyses of sacrifice in Scripture, the book shows that communion is not possible without the reconciliation attained by sacrificial self–giving love. Following the insights of St Thomas Aquinas, the author argues that all aspects of Eucharistic theology, including metaphysical doctrines such as transubstantiation, depend upon recognizing that communion cannot be separated from its sacrificial context.

The book will stimulate discussion because of its controversial critique of the dominant paradigm for Eucharistic theology, its reclamation of St Thomas Aquinas s theology of the Eucharist, and its response to Pope John Paul II s Ecclesia de Eucharistia. …

Jon D. Levenson points out that Israel, marked by desire to be in communion with the all-holy God, recognizes that such communion is possible only, after sin, through sacrificial offering.

Jeg leste i dag tidlig en artikkel skrevet av P. Cassian Folsom, O.S.B., som tar opp dette temaet. Der skriver forfatteren bl.a.:

… For some 1600 years previously, the Roman rite knew only one Eucharistic Prayer: the Roman canon.

In the average parish today, Eucharistic Prayer II is the one most frequently used, even on Sunday. Eucharistic Prayer III is also used quite often, especially on Sundays and feast days. The fourth Eucharistic prayer is hardly ever used; in part because it is long, in part because in some places in the U.S. it has been unofficially banned because of its frequent use of the word «man». The first Eucharistic Prayer, the Roman canon, which had been used exclusively in the Roman rite for well over a millennium and a half, nowadays is used almost never. As an Italian liturgical scholar puts it: «its use today is so minimal as to be statistically irrelevant».

This is a radical change in the Roman liturgy. Why aren’t more people aware of the enormity of this change? Perhaps since the canon used to be said silently, its contents and merits were known to priests, to be sure, but not to most of the laity. Hence when the Eucharistic Prayer began to be said aloud in the vernacular, with four to choose from — and the Roman canon chosen rarely, if ever — the average layman did not realize that 1600 years of tradition had suddenly vanished like a lost civilization, leaving few traces behind, and those of interest only to archaeologists and tourists.

What happened? Why did it happen? How should we respond to the new situation? These questions are the subject matter of this essay.

Til spørsmålet om hvorfor dette skjedde, skriver han bl.a.:

1. Advances in liturgical studies

The first reason is quite straightforward. Decades of scholarly research in the area of the anaphora, both eastern and western, had resulted in a considerable corpus of primary texts and a corresponding body of secondary literature. …

2. Dissatisfaction with the Roman Canon and architectural functionalism

A second reason for the change from one Eucharistic Prayer to many was dissatisfaction, on the part of some liturgical scholars, with the Roman canon. I would like to argue that there is a connection between this dissatisfaction and 20th-century architectural functionalism.

The man who best illustrates this theory is Cipriano Vagaggini. In Vagaggini’s book on the Roman canon, prepared for Study Group 10 of the Consilium (the group responsible for implementing the Council’s reform), the basic argument in favor of change is that the Roman canon is marred by serious defects of structure and theology. Vagaggini summarizes his argument in these words: «The defects are undeniable and of no small importance. The present Roman canon sins in a number of ways against those requirements of good liturgical composition and sound liturgical sense that were emphasized by the Second Vatican Council.»

The structural defects show themselves in the disorderliness of the Canon, according to Vagaggini. It gives the impression of an agglomeration of features with no apparent unity, there is a lack of logical connection of ideas, and the various prayers of intercession are arranged in an unsatisfactory way. …

Not only is the Roman Canon marred by structural defects, according to Vagaggini, but there are a number of theological defects as well. The most grievous of these theological problems is the number and disorder of epicletic-type prayers in the canon and the lack of a theology of the part played by the Holy Spirit in the Eucharist.

Liturgical historian Josef Jungmann counters this critique of Vagaggini’s by pointing out that Vagaggini is a systematic theologian who wanted to impose a certain preconceived theological structure on the Eucharistic Prayer. Since Vagaggini had a particularly keen interest in the pneumatological dimension of the liturgy, his new Eucharistic Prayers (III and IV) give a decided emphasis to the Holy Spirit.

Jungmann refers to Vagaggini’s famous book, Il senso teologico della liturgia to reinforce his argument. What we have here, says Jungmann, is the personal theology of the author, not the universal theology of the Church. …

Verken Jungmann eller Bouyer (jeg har nettopp lest dem begge) er enige i at det er noen strukturelle eller innholdsmessige problemer med første eukaristiske bønn – tvert imot, Bouyer har ikke annet enn godt å si om den. Og P. Folsom er nok en forsiktig mann, for det eneste han foreslår at man skal gjøre med denne situasjonen, er som prester å bruke første eukaristiske bønn oftere.

Jeg leste i dag ferdig Boyers bok EUCHARIST, der han tydelig skriver hvordan eukaristien best bør forstås; som en ihukommelse og takksigelse for Mirabilia Dei, Guds store frelseshandlinger. Det blir feil (skriver han) å fokusere på takken for den hellige kommunion (den kommer mer som et resultat av vår takksigelse for Guds store gjerninger og Kristi tilstedeværelse) og heller ikke på fellesskapsmåltidet (som også er et resultat av det samme). Helt på slutten av boka skriver han mye godt om den (nye, han skrev boka i 1968) tredje eukaristiske bønn (som er bygget på den galliske/spanske tradisjonen, men den andre eukaristiske bønn har han lite godt å si om; den er bygget på Hippolyts bønn, som (sier han) helt sikkert ikke har noe med den gamle romerske liturgien å gjøre. Forhåpentligvis vil jeg kunne klare å samle meg til å skrive litt mer om denne boka.

Jeg leste også i dag et intervju med Dr. Keith Lemna: Rev. Louis Bouyer: A Theological Giant – Dr. Lemna har studert Boyers bøker svært grundig, og i intervjuet sier han bl.a.:

Who was Fr. Louis Bouyer?

Dr. Lemna: Louis Bouyer was a priest of the Oratory, a convert to Catholicism from Lutheranism, which he had served as a minister, an eminent liturgiologist and historian of spirituality, an influential scholar of Newman (whose studies of Newman helped to pave the way for Newman’s eventual beatification), and, perhaps most importantly of all, one of the greatest Catholic theologians of the twentieth century.

What were some of Fr. Bouyer’s significant contributions in the realm of Catholic theology?

Dr. Lemna: Fr. Bouyer is known most of all as a scholar of liturgy and spirituality, and it is in these areas that his work has exercised its most overt impact on the course of Catholic theology as a whole. In the area of liturgy, Bouyer, himself drawing on the work of Dom Odo Casel, is the figure who is most responsible for the emphasis that has been placed in recent decades on the theme of the «Paschal Mystery» as central for understanding the mystery of the faith, and he, as much or more than anyone, oriented sacramental theologians to a focus on the liturgical event as the basis for theological reflection on the nature and meaning of the sacraments.

What were some of his key works?

Dr. Lemna: … Similarly important is his book on the Eucharist, Eucharistie, one of three seminal studies of Christian liturgy done in the twentieth century (along with Josef A. Jungmann’s The Mass of the Roman Rite, and Dom Gregory Dix’s The Shape of the Liturgy). In this book, Bouyer explores the theology and historical development of the Church’s Eucharistic prayer. He argues for the importance of developing a theology of the Eucharist based on attention to the act of the liturgy, rather than a theology about the Eucharist that takes its starting point in abstract metaphysical concepts that are then applied to the reality of the Eucharist. He shows the roots of the Christian Eucharist in Jewish Temple and synagogue practices, going beyond Casel’s thesis that the Church had borrowed its liturgical forms from the Greco-Roman mystery cults.

What influence did his work have on the Second Vatican Council?

Dr. Lemna: It is difficult to assess the precise influence that Bouyer’s work had on the council. By the time that the council had convened, many of Bouyer’s ideas had become common currency among some of the theologians who were present at the council, even if they were not influenced by Bouyer. Bouyer was a theological expert relied upon by the Church in the period surrounding the council, and he was greatly trusted by Paul VI, who appointed him to the first International Theological Commission after the council and who had wanted to name him a cardinal. Bouyer refused the offer, arguing that it would cause too much trouble for the Holy See. He had been engaged in fierce polemics with the later generation of liturgists in France, and his reputation had suffered as a result. …

What are some aspects of Fr. Bouyer’s work that are deserving of more study and consideration?

Dr. Lemna: … I think that the biggest obstacle to furthering his thought is that Bouyer wrote in a very polemical style at times, in a way that was off-putting to both «traditionalist» and «progressivist» camps in theology. But the old battles that fueled those polemics are largely a thing of the past by now, and most of the participants in those battles are dead. Bouyer could be equally sharp toward neo-Thomists, Rahnerians, and toward theologians influenced to a great extent by liberal Protestantism. …. Despite his penchant for polemics, his overall vision of the unity of Catholic doctrine, of the connection between theology and Christian life, and his unrivalled sense of the central importance of sacred liturgy for theology and for the existence of the Church stands out over and beyond all of the heated disputes. Cardinal Lustiger had said that Bouyer was perceived as «untimely» and «unwelcome» to the «very generations» to whom he was «providentially sent.» But perhaps in our time we can begin to see more clearly precisely how lucid and comprehensive—and, one might even say, «forward-looking»—was Bouyer’s vision of Catholic theology. …

Siden jeg nå for alvor begynner å lese p. Louis Bouyers bøker om liturgi (først med boken Eucharist), innser jeg at jeg nok burde ha gjort det tidligere. Jeg publiserer her innlegg på min blogg som jeg skrev for snart seks år siden, der det refereres til Bouyer og hans nokså karakteristiske jødiske synspunkter på teologien. Slik skrev jeg for seks år siden som innledning til et sitat: I John Baldovins bok (som jeg nevnte HER), som i utgangspunktet er kritisk til kritikerne av den nye messen, men som gjengir disse kritikernes synspunkter ganske så presist, er det også en beskrivelse av pave Benedikts/ kardinal Ratzingers synspunkter på liturgiforandringene, bl.a. dette:

Of all the liturgical questions on which he has written, Cardinal Ratzinger has clearly created the most stir with his attitude toward the orientation of the priest-celebrant at Mass … To understand the stance he has taken, one must appreciate his theory of the development of church architecture. Basically he has accepted the theories put forward by Louis Bouyer in his famous Liturgy and Architecture. Bouyer argued a direct link between the architecture of Jewish synagogues and the development of Christian church buildings, with the latter oriented toward the east instead of toward Jerusalem. In place of the ark containing the Torah, Christians set up the cross of Christ. Ratzinger sees in the «orientation» (literally east-facing) of Christian churches an attitude of eschatological expectation. The cross symbolizes the returning Christ, who will rise like the sun. Thus the priest in offering the sacrifice faced east and the altar was placed near the eastern apse of the church building. Ratzinger emphatically insists that in the early church it was never a question of «facing the people» (versus populum) or not but rather one of orientation. …

For Ratzinger the position of the altar is «at the center of the postconciliar debate.» Having the priest face the people has caused a fundamental shift, essentially a novelty, in the meaning of the liturgy which now looks like a communal meal.» As we have seen above, he rejects this as a one-sided interpretation that fails to take the sacrifice aspect of the liturgy into account. To make matters worse, the liturgy now becomes primarily a matter of roles, since the priest’s role has been so greatly accentuated and others need to have their functions too. The problem with all this for Ratzinger is that the liturgy devolves info a «self-enclosed circle» rather than worship directed toward God. There is some accuracy to his criticism of a liturgy that has focused more and more on the role-and personality of the priest. The great irony here is that in the pre-Vatican II liturgy the priest was not all that important (except when he sang badly). The «success» of the liturgy had little to do with his personality, except for the fact that people might prefer the piety and devotion of one priest over another. Now, I would agree, too much can depend on the personality of the priest, who must exercise enormous self-discipline in not succumbing to the temptation to put himself forward.

In his reply to Pierre-Marie Gy, Ratzinger has recently reiterated that he does not necessarily want a return to the eastward position. He regards his own stance as rather nuanced. It involves three factors:

1. He thinks there should be a separate space for the proclamation of the Word.

2. In large churches where the apse altar is a great distance from the people, an altar should be constructed closer to them.

3. Altars need not be «turned around» again. Instead, the «liturgical East» can be symbolized by a cross in the center of the altar toward which both priest and people face.

He puts the last point this way: «To be able to fix our gaze, all of us together, on him who is the Creator, the one who receives US into the cosmic liturgy, and who shows us also the path of history; this is what would enable us to recover the dimension of deep unity that exists between the priest and the faithful within their common priesthood.” Elsewhere he had already regarded moving the cross on the altar to one side an absurd phenomenon in the liturgical reform. I think it is fair to say, however, that he wishes that the altars had never been «turned around.»

Jeg begynner nå å lese p Louis Louis Bouyers bok EUCHARIST, der han i løpet av nesten 500 sider går gjennom utviklingen og forståelsen av messen. Bouyers stil er veldig annerledes enn Jungmanns, som var svært saklig og lite kritisk kommenterende til andre forskeres bidrag. Bouyer har en ganske annen kontroversiell og aktuell stil. Slik begynner han f.eks. forordet, som han skrev i juni 1966 og januar 1968 (2. utgave):

Jeg begynner nå å lese p Louis Louis Bouyers bok EUCHARIST, der han i løpet av nesten 500 sider går gjennom utviklingen og forståelsen av messen. Bouyers stil er veldig annerledes enn Jungmanns, som var svært saklig og lite kritisk kommenterende til andre forskeres bidrag. Bouyer har en ganske annen kontroversiell og aktuell stil. Slik begynner han f.eks. forordet, som han skrev i juni 1966 og januar 1968 (2. utgave):

This book is the result of more than twenty years of research. It is appearing at a moment when the understanding of the traditional Eucharistic prayer, and especially the canon of the Roman mass, is more timely than ever. On one hand it has been a very long time since we have seen such lively and widespread desire in the Catholic Church to rediscover a “eucharist” that is fully living and real. Yet, unfortunately, there has also never been a time when we have been so confidently presented with such fantastic theories that, once put into practice, would make us lose practically everything of authentic tradition that we have still preserved. May this volume contribute its part towards promoting this renewal and discouraging an ignorant and pretentious anarchy that could mean its downfall. …

I 1968 har messen og holdningene til den allerede forandret seg en del, og på s 10 skriver Bouyer ganske skarpt om resultatet av enkelte forandringer:

… we may congratulate ourselves on our discovery of the collective sense of the eucharistic celebration through a return to notions of the eucharistic sacrifice that imply our own participation. But it is already a very bad sign that the values of adoration and contemplation, which yesterday focused on a eucharistic devotion that was in fact foreign to the eucharist, seem hardly to have come back to our celebration of it, but have rather simply vanished into thin air …

Han referer her til at eukaristisk tilbedelse (utenom messen) ikke er en særlig sentral praksis, i forhold til selve messefeiringen, selve frembæringen av messens offer. Men når man motarbeider gamle, fromme tradisjoner, uten å erstatte dem med noe nytt, blir jo resultatet ganske katastrofalt.

Vårt Land bruker dette bildet til å illustrere ulike former for gudstjenesteliv i Den norske kirke, og det er fra Uranienborg kirke i Oslo – artikkelen ble publisert i fjor, men de lenker til den i dag. For en katolikk er det underlig – og spesielt for meg, som akkurat nå leser om den katolske messeliturgien gjennom tidene – å kunne observere at det nesten alle steder i verden (og absolutt alle steder i Norge) ville være uaktuelt å bruke en kirke som ser så høytidelig ut. For: korpartiet er trukket et ganske langt stykke bort fra folket, det er en skjerm som deler av koret, man har et alter som er vendt bort fra folket, man har en alterring der folk kneler når de mottar nattverd/ kommunion – og til og med en nokså høy prekestol. I Norge ble kirker som så slik ut modernisert på 70-tallet, og nye kirker ble bygget med et frittstående bordalter, og uten kommunionsbenk og prekestol. Det er egentlig ganske sjokkerende at katolikkene oppførte seg så misforstått moderne.

Jeg liker riktignok heller ikke selv alle gamle kirkerom, og avstanden mellom folket og presten/ alteret opplever jeg som ganske viktig. I en full kirke er en forholdsvis stor avstand naturlig, i en messe med bare noen få til stede er stor avstand ganske ubehagelig – syns jeg. Eamon Duffy skiver om katolsk kirkeliv i England rundt 1500, at i søndagens høymesse ble høyalteret – som var trukket en godt stykke tilbake inn i et kor delt av med en skjerm – alltid brukt, men også her var det ganske mye kontakt mellom den store folkemengden i kirkerommet og presten; ved prosesjonen gjennom kirkerommet og stenkingen med vievann i starten av messen, ved preken, forbønner, kunngjøringer, der presten stod godt synlig for menigheten (og snakket engelsk), da alle kom fram og kysset «pax-bredet» (som fredshilsen), når folk (av og til) mottok kommunion, og ved utdelingen av velsignet brød etter messen (den tradisjonen hadde holdt seg). Ved ukedagsmessene var situasjonen en helt annen, skriver Duffy, da brukte man sidealterne (og messene ble gjerne feiret for en avdød, eller for en av de mange foreningene som fantes i menigheten) og folk stod helt inntil presten mens han feiret messen.

I England var også skjermene foran koret svært viktige i nesten alle kirker. De kalles rood screen, der rood betyr krusifiks, som stod på toppen av skjermen (se bildet under). Ved reformasjonen ble krusifiksene revet ned, men skjermene ble ofte stående (om de ikke hadde for mange helgenbilder). Les om rood screens på Wikipedia her.

Jungman skriver (på s 223 av bind to av messens historie) at det er i den første bønnen etter konsekrasjonen at messens offerhandling uttrykkes aller tydeligst. Det er i bønnen som kalles Unde et memores, og som på norsk lyder slik:

Vi minnes nå, Herre, vi dine tjenere og hele ditt hellige folk, den samme Kristi, din Sønns, vår Herres, salige lidelse. men også hans oppstandelse fra de døde og hans herlige himmelferd, og bærer fram for din opphøyede majestet av dine goder og gaver et + rent offer, et + hellig offer, et + lytefritt offer, det evige livs hellige + brød og den, evige + frelses kalk.

Om denne bønnen skriver Jungmann (jeg har selv uthevet deler av teksten):

The second point that is expressed in the Unde et memores and then taken up and developed in the following prayers, is the oblation or offering. Here we have the central sacrificial prayer of the entire Mass, the foremost liturgical expression of the fact that the Mass is actually a sacrifice. In this connection it is to be noted that there is reference here exclusively to a sacrifice offered up by the Church. Christ, the high-priest, remains wholly in the background. It is only in the ceremonies of the consecration, when the priest all at once starts to present our Lord’s actions step by step, acting as Christ’s mouthpiece in reciting the words of transubstantiation—only here is the veil momentarily withdrawn from the profound depths of this mystery. But now it is once more the Church, the attendant congregation, that speaks and acts. And it is the Church in concreto, manifest plainly in its membership; it is the congregation composed of the “servants” of God and the “holy people,” which has already appeared as the subject of the remembrance in the anamnesis. To show how aware the Church is of what she is, we must point to the significant words here used, plebs sancta, words which bring to the fore the sacerdotal dignity of the people of God in the sense implied by 1 Peter 2:5, 9.

Canon fortsetter med to bønnen til som også tydelig snakker om offeret; om hvordan Gud bes om å ta imot vårt offer som han mottok Abels, Abrahams og Melkisedeks, og (i siste bønn) om at han vil la sin engel bærer offeret fram for seg i himmelen:

Verdiges med nådig og mildt åsyn å se ned på dette offer og motta det, likesom du med velvilje tok mot din rettferdige tjener Abels offer og vår patriark `Abrahams offer og det hellige og lytefri offer som din øversteprest Melkisedek bar fram for deg.

Allmektige Gud, vi ber deg ydmykt, la dette offer ved din hellige engels hender bæres fram til ditt opphøyede alter for din guddommelige majestets åsyn, så alle vi som med del i dette alter tar imot din Sønns høyhellige + legeme og + blod, må bli fylt med + all himmelsk velsignelse og nåde. Ved ham, Kristus, vår Herre. Amen.

Jeg leser nå gjennom Josef Jungmanns beskrivelser av absolutt alle deler av (den tradisjonelle, siden han skriver i 1949) messen, og da jeg for noen dager siden leste gjennom hans grundige beskrivelse av offertoriet (som ble så voldsomt kritisert på 60-tallet og helt forandret i 1969), ble jeg noe overrasket over hans konklusjon – siden Jungmann regnes for å være den største autoriteten som ledet til de store forandringene i messen etter konsilet. For han konkluderer slik i kapittelet om offertoriet (s 100, i bind 2 av The Mass of the Roman Rite):

… If the first prayer includes a phrase, hanc immaculatam hostiam, in reference to the bread, this may have been intended by the medieval composer for the holy Eucharist. But objectively we can refer the phrase just as well to the simple earthly bread, and with the same right that we apply the words of the canon, sanctam sacrificium, immaculatam hostiam to the sacrifice of Melchisedech. Something like this holds true also for the words calix salutaris in the formula for the chalice. Even on this threshold of the sacrifice our chalice is at least as holy and wholesome as the thanksgiving cup of the singer in Psalm 115, from whom the words are borrowed. Of course it is self-evident that when we say these prayers the higher destiny of our gifts is always kept in view.

Seen thus as a complete unit, we have no reason to deplore the development of the liturgical structure as we have it in the offertory, not at least if we are ready to acknowledge in the Mass not only an activity on God’s part, but also an act of a human being who is called by God and who hastens with his earthly gifts to meet his Creator.

Dette var og er bønner presten stort sett sier stille, derfor skal jeg vise hvordan dette er blitt forandret fra den tradisjonelle messen til den nye messen. Jeg skriver på norsk det presten sier på latin – norsk og latinsk tekst for hele messen fins her.

Under offertoriet sa presten da han presenterte brødet:

Ta imot, hellige Fader, allmektige evige Gud, dette uplettede offer, som jeg, din uverdige tjener, bærer fram til deg, min levende og sanne Gud, for mine utallige synder, feil, forsømmelser, og også for alle som er til stede her, men også for alle troende kristne, levende og døde, så dette offer for meg og for dem må bli til frelse og evig liv. Amen.

Dette er nå blitt erstattet av (en jødisk bønn, som ikke er blitt brukt i katolsk liturgi tidligere):

Velsignet er du, Herre, all skapnings Gud. Av din rikdom har vi mottatt det brød som vi bærer frem for deg, en frukt av jorden og av menneskers arbeid, som for oss blir livets brød. (Alle svarer: Velsignet være Gud i evighet.)

Videre sa presten da han presenterte kalken:

Vi bærer fram for deg, Herre, frelsens kalk, idet vi påkaller din nåde, så den med vellukt må stige opp for din guddommelige majestets åsyn til frelse for oss og hele verden. Amen.

Dette er nå blitt erstattet av:

Velsignet er du, Herre, all skapnings Gud. Av din rikdom har vi mottatt den vin som vi bærer frem for deg, en frukt av vintreet og av menneskers arbeid, som for oss blir frelsens kalk. (Alle svarer: Velsignet være Gud i evighet.)

Presten sier så videre to bønner (den første er beholdt i dag i forkortet form, den andre er helt borte):

I ydmykhets ånd og med botefullt sinn ber vi deg: ta imot oss, Herre, og la dette offer i dag fullbyrdes slik for ditt åsyn at det tekkes deg, Herre og Gud.

Kom Helliggjører, allmektige evige Gud, og velsign + dette offer som er gjort rede for ditt hellige navn.

Som siste bønn før «Orate fratres» sa så presten en bønn som også er blitt helt borte:

Ta mot dette offer, hellige Treenighet, det vi bærer fram for deg til minne om Vår Herres Jesu Kristi lidelse, oppstandelse og himmelferd, og til ære for den salige Maria, alltid jomfru, den hellige Johannes døperen og de hellige apostler Peter og Paulus og til ære for disse og for alle helgener, så det må bli til heder for dem, men til frelse for oss, og at de, som vi feirer minnet om på jorden, må verdiges å be for oss i himmelen. Ved ham, Kristus, vår Herre. Amen