Nå ser det ut til at bispesynoden i Roma har tatt opp de samme problemstillingene – mer radikalt og grunnleggende. John Allen skriver om hvordan disse to spørsmåla er blitt diskutert på en ganske grunnleggende måte, og at biskopene ikke ser ut til å nøye seg med enkle eller “moderne” svar. Slik spissformulerer han det:»

The Historical-Critical Method

If all that mattered on this point were generalizations, there would be no problem. Some formula like the following would command almost overwhelming assent: The historical-critical method is valuable, but it’s not enough. It has to be integrated into the broader theological reflection of the church, which implies that theologians and exegetes need to work and play well together.

The devil, however, is in the details. Some in the synod clearly strike a more positive tone with regard to academic study of the Bible, using the essentially secular tools of historical research and literary criticism, than others. Levada characterized the contrast: “Some have criticized the historical-critical method, on the grounds that it’s difficult to overcome the philosophical suppositions which formed its basis for many of the method’s original followers,” he said. “Others see it as a useful tool for coming to a better understanding of the literal and historical sense of scripture.”

In his lone talk to the synod so far, Pope Benedict XVI touched on precisely this point, essentially arguing that scholars using the historical-critical method need to take the faith of the church as their point of departure.

On this point, two challenges present themselves.

First, the proper balanced has to be struck in the synod’s concluding documents. If there’s too much criticism of exegetes and the historical-critical method, Catholic Biblical scholars may feel under attack, or that the clock is being rolled back on tools they now take for granted. If the language is too soft, however, then the clear desire for a more “theological” reading of scripture could get lost in the mush.

Second, there’s the practical question of how, exactly, to put theologians and exegetes into deeper conversation, especially given the hyper-compartmentalized nature of academic life these days. This may well be the point upon which much drama turns—will the synod restrict itself to a fervorino about the relationship between exegesis and theology, simply echoing the basic points made by Pope Benedict XVI on Tuesday, or will it actually offer concrete suggestions for fostering closer links among Biblical specialists, theologians, and pastors?

Basilian Fr. Thomas Rosica, a Canadian who’s handling press briefings for the synod in English, and who is also a biblical scholar himself, offered a memorable metaphor for what’s at stake.

“Most of us were trained as surgeons,” he said on Thursday, by which he meant that exegetes learn to make very precise cuts on the Biblical text—determining what the exact meaning of a given verb form is, for example, or detailing the social contexts of the Johannine and Lucan communities.

“What we sometimes forgot is that we’re operating on a living body, not a corpse,” Rosica said. “We’re supposed to be heart surgeons, not coroners. Success is defined by whether the body survives the surgery.”

Inerrancy of the Bible

Some bishops, such as Cardinal George Pell of Sydney, Australia, have floated the idea that the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith produce a document on the inerrancy of the Bible, in order to resolve what has been an open question since the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) and its document on divine revelation, Dei Verbum.

This point gets technical in a hurry, but in essence, here’s what’s at stake: How much of the Bible is “inspired” and free from error? Is it just what one might call the Bible’s “theological” content, meaning what it teaches about salvation? Or is the whole Bible inerrant, and therefore “true,” even if that doesn’t necessarily mean literally, factually true?

Cardinal Francis George of Chicago, widely seen as one of the leading thinkers at the senior levels of the church, said in an interview this week that the second option better represents “where we’re at today,” but acknowledged that the issue hasn’t been resolved.

There’s something of a Scylla and Charybdis dynamic inherent to this debate. Veer too far towards saying that only the theological parts of the Bible are inspired, and it can seem like the church is flirting with skepticism; go too far toward saying inerrancy applies to every jot and tittle, and it can end in a kind of Catholic fundamentalism.

Whatever view one takes, there’s also the practical question of whether now is the right time for the Vatican to say something. Though this is admittedly a fairly cynical view of things, it’s often the case that people clamor for a Vatican statement when they think they’ll get the answer they want; otherwise, they tend to suggest that it’s not yet “opportune” to put out a document.

Exactly how the synod phrases its recommendation on this point—should it choose to make one at all—will therefore be fascinating to watch.

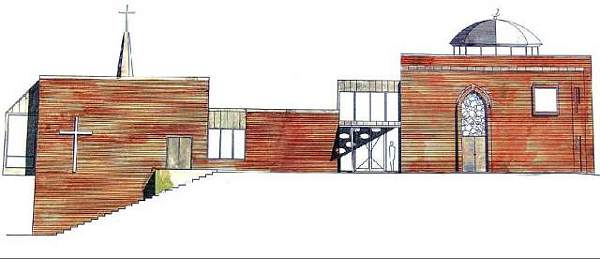

Her snakker man altså om at de kan bli tatt opp i Kirken etter bestemmelsene i pave Benedikts dokument «Anglicanorum Cætibus», der de kan tas opp sammen i grupper (prest og menighet) og får beholde noe av sin egen liturgiske tradisjon. (Dvs. sine flotte liturgier, og også (får vi håpe) sine flotte kirker og altere – se bildet over.)

Her snakker man altså om at de kan bli tatt opp i Kirken etter bestemmelsene i pave Benedikts dokument «Anglicanorum Cætibus», der de kan tas opp sammen i grupper (prest og menighet) og får beholde noe av sin egen liturgiske tradisjon. (Dvs. sine flotte liturgier, og også (får vi håpe) sine flotte kirker og altere – se bildet over.)  I Nasjonalgalleriet her i Oslo vises fra 24. september 2010 til 16. januar 2011 mange flotte skatter fra den ortodokse kirke i Russland. Og i morgen, mellom to søndagsmesser, skal jeg benytte anledningen til å få en omvisning blant skattene.

I Nasjonalgalleriet her i Oslo vises fra 24. september 2010 til 16. januar 2011 mange flotte skatter fra den ortodokse kirke i Russland. Og i morgen, mellom to søndagsmesser, skal jeg benytte anledningen til å få en omvisning blant skattene.  I går kveld var det museumsnatt i Oslo, og mens min kone benyttet anledningen til å se flere utstillinger, fikk jeg se én, som til gjengjeld var svært interessant. Det var leiligheten der Henrik Ibsen levde sine siste 10 år, rett ved slottet i Oslo. Jeg visste ikke at han levde så luksuriøst; men leiligheten var svært stor, 350 m2, flunkende ny og tipp topp moderne, og hadde en årsleie på astronmiske 2500 kr, noe som vil tilsvare over en halv million kroner i dag. Slik leser vi på

I går kveld var det museumsnatt i Oslo, og mens min kone benyttet anledningen til å se flere utstillinger, fikk jeg se én, som til gjengjeld var svært interessant. Det var leiligheten der Henrik Ibsen levde sine siste 10 år, rett ved slottet i Oslo. Jeg visste ikke at han levde så luksuriøst; men leiligheten var svært stor, 350 m2, flunkende ny og tipp topp moderne, og hadde en årsleie på astronmiske 2500 kr, noe som vil tilsvare over en halv million kroner i dag. Slik leser vi på

Menighetsfakturltet ordienteren om en doktordisputas som går av stabelen fredag 8. oktober 2010 kl. 1015. Da vil doktorand Helene Lund offentlig forsvare sin avhandling ”Conflicting Ecclesiologies. Exploring the Ecclesiological Discourse in the Special Commission on Orthodox Participation in the World Council of Churches from 1998 to 2002”.

Menighetsfakturltet ordienteren om en doktordisputas som går av stabelen fredag 8. oktober 2010 kl. 1015. Da vil doktorand Helene Lund offentlig forsvare sin avhandling ”Conflicting Ecclesiologies. Exploring the Ecclesiological Discourse in the Special Commission on Orthodox Participation in the World Council of Churches from 1998 to 2002”.