Som en fortsettelse på forrige innlegg, er det på sin plass å påpeke at det er 11- til 1200 år siden kanonbønnen begynte å bli sagt stille av presten. Slik beskriver Michael Davies utviklinga:

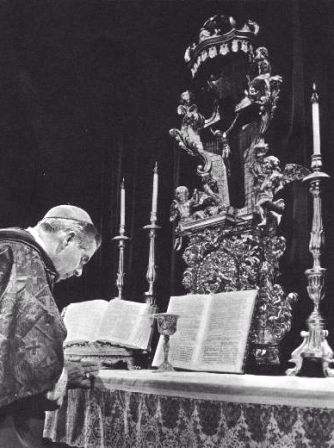

… For a long time the Canon was said aloud, probably to a recitative, but simpler, tone like the Preface. Recitation in a low voice appears towards the middle of the eighth century, and in the ninth century with Ordo Romanus the silent recitation became obligatory. In the east the practice was adopted much earlier. Everywhere the tendency was to surround the Canon with respect and a sense of mystery and to reserve it to the celebrant alone.

Father Fortescue believes that a practical reason accounts for the adoption of the silent Canon: «The Sanctus sung by the choir took some time; meanwhile the celebrant went on with the prayer, which in that case had to be said silently. So it became a custom, a tradition, and later mystic reasons were found for it.»

What is certain is that the transition must have taken place under the guidance , of the Holy Ghost and the reason is not hard to find-there could be no more appropriate manifestation both of the nature of the Canon and the awesome powers of the sacrificing priest. This is made clear in the quotation from Father Jungmann which began this chapter. Similar sentiments expressed by other Catholic authors are not hard to find-and the Catholic who would have questioned them before Vatican II would have been rare indeed. …

Jeg har ingen egen erfaring å bygge på, men jeg har vanskelig for å tro at lekfolket skulle ha noen problemer med at denne (mest høytidelige) delen av messen ble sagt stille – de som husker tilbake så langt, må gjerne informere meg/oss. Jeg ser det heller slik at dette hører sammen med at presten skulle vende seg mot folket, også i de delene av messen der han tydelig ber til Gud. Det gir jo ingen mening at man kaster ut det gamle alteret, setter inn et nytt bordalter, presten står nå vendt mot folket, men snakker fortsatt med hviskende stemme; da må han jo snakke slik at folk kan høre ham!

Tidligere fokuserte man på at presten ba bønnene, og spesielt den eukaristike bønn, til Gud, og da var det naturlig at han også vendte seg til Gud (det var også helt narurlig i min lutherske oppvekst). Men når fokus blir flyttet fra bønn til Gud – ja, et offer båret fram for Gud – til et nattverdsmåltid, da følger både retning og stemmebruk med på kjøpet. (Jeg må innrømme at jeg finner det litt forstyrrende, spesielt i små kapeller, å stå rett foran mennesker – og knapt kunne unngå å se på dem, et krusifiks foran meg hjelper bare delvis – når jeg ber til Gud.)

Michael Davies skriver også ting i dette kapittelet, som jeg ikke kan være enig i. Han skriver (og det gjør han gjennom hele boka) at katolikkene forandret dette (kanon med lav eller kraftig stemme) for å tekkes protestantene. Der tror jeg han tar feil; dette var ikke den viktigste begrunnelsen. Det var heller det man noen ganger kaller arkeologisme; at man vil gå tilbake til noe eldre, som man regner som bedre (selv om man også misforstod mye av dette på 60-tallet). Man tenkte at katolikker de første 600-800 år feiret messen først og fremst som et nattverdmåltid (med fokus på måltid), før middelalderen kom og ødela.

Den liturgiske bevegelsen (som begynte godt, men etter hvert løp løpsk) ønsket å forandre dagens liturgi slik at den stemte bedre med den tradisjonelle. Av to grunner ble de liturgiske forandringene mislykket: 1) de misforstod Kirkens gamle praksis og 2) de tok ikke hensyn til at Kirken, ledet av Den hellige Ånd, utviklet en tjenlig og god liturgi – som nok trengte justering, men som det var helt feil å kaste vrak på.

Vi var i Roma sist lørsdag (19/3) fram til kl 14, men visste ikke om denne messen i Pantheon (Santa Maria ad Martyres).

Vi var i Roma sist lørsdag (19/3) fram til kl 14, men visste ikke om denne messen i Pantheon (Santa Maria ad Martyres).