Mer om forståelsen av messeofferet

Shawn Tribe presiserer stadig hva han mente med innlegget (som jeg nevnte her) om messen som offer. Han skriver i en kommentar til sitt eget innlegg:

Just to keep things in focus, as I’ve noted above, being «Mass-centered» is not really the issue I’ve tried to speak to, but rather how the Mass is being understood. One could give primary focus to the Mass and still fall into the issue I am presenting.

…

Han skriver også noe som jeg har tenkt mange ganger, og gjerne selv kunne ha formulert akkurat som han selv gjør det:

I’ve known people who speak so (use the term «Sacrifice of the Mass») but yet still have a view of the Mass which still sees it as -essentially- about encountering Christ in the Blessed Sacrament through adoration at the moment of consecration and receipt of Holy Communion. I think in those instances it is a case of traditional language having been adopted, but without necessarily a full comprehension of the theological underpinnings and meaning of those terms.

This is why I say that I believe the Trinitarian dimension needs to be expounded upon, as does a

typological consideration between the Old and New Testament. These will help to give those theological underpinnings and help us to understand the Mass in the light of the big picture of salvation history and the heavenly liturgy.

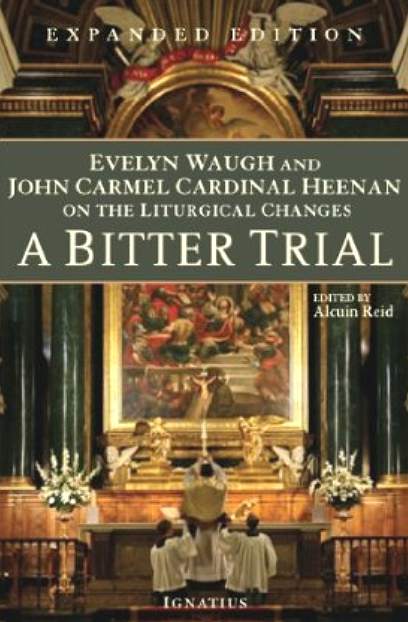

I oktober i år utgis boka: A Bitter Trial: Evelyn Waugh and John Cardinal Heenan on the Liturgical Changes på Ignatius Press i USA. Det er den engelske forfatteren Evelyn Waughs problemer med liturgiforandringene og hans korrespondanse med kardinal Heenan som tas opp i boka på 101 sider.

I oktober i år utgis boka: A Bitter Trial: Evelyn Waugh and John Cardinal Heenan on the Liturgical Changes på Ignatius Press i USA. Det er den engelske forfatteren Evelyn Waughs problemer med liturgiforandringene og hans korrespondanse med kardinal Heenan som tas opp i boka på 101 sider.