Liturgistridighetene i engelskspråklige land har roet seg

John Allen skriver en artikkel med overskrift ‘Liturgy wars’ have gone quiet, but they’ve hardly gone away, der han bl.a. sier:

This week, a press release washed up in my in-box from the International Commission on English in the Liturgy (ICEL), about a recent visit to their offices by a Vatican official. ICEL is a mixed commission of bishops’ conferences in countries where English is used in the liturgy, and its job is to translate texts for worship.

My finger was poised on the delete button, when it suddenly struck me just how remarkable it is that ICEL is no longer a hot potato. Not so long ago, at the peak of what came to be known as the “liturgy wars,” that definitely wasn’t the case.

The term “liturgy wars” refers to a series of battles over the sound, look and feel of Catholic worship in English, which crested in the 1990s and 2000s.

The battle lines broke between progressives in favor of a reformed, “Vatican II” style, reflecting modern sensibilities and new theological insights, and conservatives who felt the post-Vatican II overhaul of the liturgy gave too much away to secular modernity, often employing pretty-sounding ecumenical formulae dubious in terms of fidelity to both tradition and the actual Latin text.

Adding fuel to the fire were two other factors:

In part, liturgical controversies pivot on aesthetics – judgments about what’s poetic vs. pedantic, what’s artful vs. awful, what sounds or looks good. Since all that’s basically subjective, there’s just no way to make everyone happy. Unlike other topics, where most people don’t consider themselves experts, everybody’s been to Mass, and so everybody has an opinion about how it ought to be done.

Incalculable hours were spent over two decades debating issues such as inclusive language, … or whether the Latin phrase pro multis in the Eucharistic prayer should be “for all” or “for many.” Countless conferences were held, essays written, blogs posted, and it seemed for a while the debate would never end. …

Allen syns altså at debatten har roet seg veldig mye, men bildet (under) som illustrerer artikkelen, viser likevel minst tre liturgiske feil: Presten skal dekke til skjorten/ halsen med en hvit amikt, han skal ikke ha stolaen over messehakelen, og diakonen ved hans side skal ikke løfte hendene til bønn.

På liturgibloggen Pray Tell har man tatt opp tråden fra denne artikkelen, og folk er sterkt uenige. Noen liker fortsatt den nye engelske oversettelsen av messen svært dårlig, mens en nokså nyordinert prest skriver:

I was ordained to the priesthood in 2013. I didn’t have to memorize the presidential prayers of the previous translation because the texts for MR3 were, thankfully, already out. So I have ONLY presided with the present translation, though I had been Catholic for the previous three decades, too.

The VAST majority of younger priests I know (American Midwest and South) are grateful for the new translation and consider it a marked improvement over the previous edition. Not that it doesn’t have its substantial flaws, but an overall improvement. I find that priests and liturgists have strong feelings about it, but most people have settled into it and are fine with it. I agree that changing it again any time very soon would be a mistake, even if another translation was significantly better.

I find the present translation to have substantially better, richer imagery, but it is more difficult to verbalize. …

Which is just as well. In fact, Mother Teresa is of interest to me not because she was enlightened more than others on matters spiritual. On the contrary, my continued interest in her is explained particularly because she herself was in the dark all her life. Not many religious “professionals” would admit this “deficiency” as Mother Teresa did in her talks and writings to her spiritual directors. Honesty and integrity separate her from theological hypocrisy often manifested at institutional level.

Which is just as well. In fact, Mother Teresa is of interest to me not because she was enlightened more than others on matters spiritual. On the contrary, my continued interest in her is explained particularly because she herself was in the dark all her life. Not many religious “professionals” would admit this “deficiency” as Mother Teresa did in her talks and writings to her spiritual directors. Honesty and integrity separate her from theological hypocrisy often manifested at institutional level.

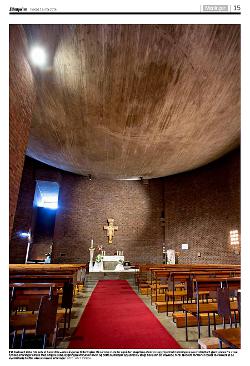

… Mellom boligblokkene på Enerhaugen ligger et upåaktet storverk i norsk arkitektur: St. Hallvard kirke og kloster, tegnet av Kjell Lund i 1966. Bygningens eksteriør er lukket, formet som en hvilende kube. Tung og urokkelig står den rett på grunnfjellet, veggene er i grov tegl, vinduene er små glugger og inngangene er kilt inn som dype snitt i massen. Interiøret er omsluttende i form av en sylinder, med varmrøde teglvegger som kretser om rommet som i en hule, der lyset siver inn gjennom smale vertikalsnitt i overflaten. Taket er synkende og faller som en knyttneve ned i rommet i form av en omvendt betongkuppel, men stiger så igjen til den ene siden i retning av alteret.

… Mellom boligblokkene på Enerhaugen ligger et upåaktet storverk i norsk arkitektur: St. Hallvard kirke og kloster, tegnet av Kjell Lund i 1966. Bygningens eksteriør er lukket, formet som en hvilende kube. Tung og urokkelig står den rett på grunnfjellet, veggene er i grov tegl, vinduene er små glugger og inngangene er kilt inn som dype snitt i massen. Interiøret er omsluttende i form av en sylinder, med varmrøde teglvegger som kretser om rommet som i en hule, der lyset siver inn gjennom smale vertikalsnitt i overflaten. Taket er synkende og faller som en knyttneve ned i rommet i form av en omvendt betongkuppel, men stiger så igjen til den ene siden i retning av alteret. Alle disse trekkene er med på å tolke klosterets funksjon: Den lukkede kuben viser til munkenes avsondrethet fra utenverden, sylinderen til deres konsentrasjon om bønn og det synkende taket tolker himmelens tilstedeværelse, mens stigningen løfter blikket mot gudstjenestens fokus.

Alle disse trekkene er med på å tolke klosterets funksjon: Den lukkede kuben viser til munkenes avsondrethet fra utenverden, sylinderen til deres konsentrasjon om bønn og det synkende taket tolker himmelens tilstedeværelse, mens stigningen løfter blikket mot gudstjenestens fokus.